Roman army

The army and the legions in particular played a key role in the history of Rome. They are usually usually identified with a highly organized, highly professional and rigorously disciplined military force, but this stereotype is only true to life in one of the historical periods observed in its evolution:

- During the monarchy and the end of the second century BC, the army was organized around a system of militia, composed entirely of Roman citizens recruited for weapons according to their wealth, typically farmers with sufficient properties to acquire their arms and their equipment itself. Military service was not a profession but a service that the state should cives remaining and released when the military campaign ended. In this early period it is difficult to get into the details, because the available information does not allow back beyond the middle of the republican period.

- From the first century BC, the army was professional. Territorial expansion caused wars rid themselves increasingly far from Rome, demanding large garrisons incompatible with the system of people's militia. The equipment and weapons were provided by the state and therefore, thereafter, the legions received a large contingent of men, generally poor, who saw the army as an opportunity to make a living on a military career.

- Between the III and V AD, the army maintained the characteristics of altoimperial period, but with the vast borders had to face growing external threats and internal stresses generated by the constant civil war situations. During the late Empire legions they remained professional units, but very different in size, structure and tactics to what had been his predecessor functions. The most important military reforms were carried out by Diocletian and Constantine the Great.

Evolution

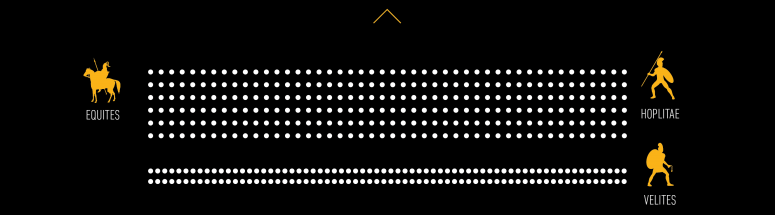

At some point in its history, the Romans adopted the tactics of the hoplite phalanx, probably introduced in Italy by Greek colonists.

Hoplites, whose name derives from the circular shield of about 90 centimeters in diameter that protected the left flank (hoplon), were lancers heavily armed and organized in close formation, so that its right side, devoid of protection, saw at least partially covered by the shield of a partner.

Its aim was to approach the enemy and force the battle always moving in step with the intention to break through with spears among the enemy ranks. Lancers were deployed in front of 500 soldiers for 8 bottom lines, the first six of hoplites (heavy infantry) and the last two of velites (light Infantry). His tactical principle was based on the direct clash, unreservedly and with a little large light cavalry forming a solid wall of shields sticking spears pointing forward. Hoplites, 3,000 in total, were supported by javelin throwers and slingers served as auxiliary cavalry troop in the persecutions.

The hoplitic fight involved much tension and violence that it made necessary for the phalanges were deep: the deeper it was a phalanx, the greater its ability to continue fighting.

Warriors second row had the chance to nail their spears above the shoulders of his teammates in the lead, who replaced in case of low, but the men who were behind could not join the fight: his main role was to support the fighting front, intimidate the enemy and, perhaps most important, prevent the escape of the soldiers in the front row.

On the battlefield, the phalanx was a military unit very consistent but low mobility and difficult to maneuver. The phalanx formation suited to fighting on level ground, so as Rome did not leave Lazio tactics provisions were not changed, but was easily defeated when he had to go out and fight on uneven terrain.

During the reign of Servius Tullius, the sixth of the seven kings of Rome (578-534 BC), there was a fundamental reform of the army based on the structure of the comitia centuriata and economic ability of soldiers, to be paid the weapons and equipment.

Based on the census of all citizens in adulthood, property values was calculated and based on that value will be divided into five classes.

The most outstanding citizens (equites) were recruited for the cavalry and came to occupy the positions of the army with the rank of officer. Others, distributed according to their kind, possessed the following weapons:

- 1st Class: circular shield, helmet, gladius, pilum, greaves, armor and breastplates of bronze.

- 2nd class: oval shield, helmet, gladius, pilum, bronze greaves and chest.

- 3rd class: shield, helmet, gladius, pilum and greaves.

- 4th class: perhaps you shield small, gladius and pilum.

- 5th class: honda.

The first class seems to have been reserved for fully armed hoplites, which has led to the suggestion that these men would form the original phalanx and the remaining classes were added later, as the population and prosperity grew over the years.

Each of the classes was organized into centuries of variable size divided by half iuniores and seniores depending on the age of the soldiers.

The total number of centuries was 170 at 80 first class, 20 second, third and fourth classes and fifth class 30.

In these centuries it had to add 18 of equites, 2 engineers and 2 musicians.

For the total count it is also scoring one century of proletarii (the capiti censi that did not appear in the census), but because citizens who had no financial capacity to afford the most rudimentary equipment, were not required to serve in the army.

The soldiers were recruited from Roman citizens only and only when the war situation required it, being licensed immediately upon the need ceased.

After the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome, much of the class was followed in exile. That made during the early years of the Republic the military potential of the city resented.

In this situation, the Senate was forced to make structural changes, the most important of which was dispensed with phalanx and replaced by legion. The reform, still based on the classification of Servius Tulius (the classification was updated after 312 BC), was a revolutionary change: the division of the army into maniples and centuries.

The first legions

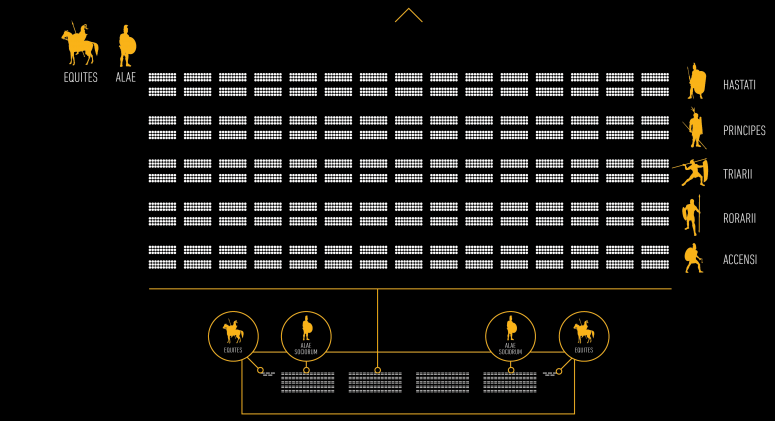

Legion as a new form of military organization appeared during the Samnite Wars (343-290 BC) after suffering a series of humiliating defeats, culminating with the delivery of an entire army without resistance in Caudine Forks (321 BC), the Romans abandoned phalanx forever. Thereafter, each legion was organized in three lines (hastati, principes and triarii) fifteen maniples each in turn divided into two centuries of 30 men. These forces had to add the alae sociorum (auxiliary troops like a legion size), the cavalry (10 turmae organized in 3 rows of 10 equites each and spread half on the flanks of the army) and light infantry troops (accensi and rorarii).

Accensi (fifth class) were the light infantry of the early days of the Republic and were located in the rear of the army, behind the first line of hastati, the second of principes, the third of triarii and fourth of rorarii. They fought in open formation training its support to the heaviest troops, often occupying the places left by the soldiers fallen in combat. After the Second Punic War, they were absorbed by velites.

Rorarii (fourth class) with similar functions as accensi, may participate in the final phase of the struggle with the triarii. After the Second Punic War, they were also absorbed by velites.

Triarii (third class): if the situation was desperate, the triarii supported by rorarii and accensi engaged in combat or, where appropriate, were in charge of organizing the retreat.

Principes (first class)

Hastati (second class): members of the second class stood in front of the first because hastati were armed with pila, to be launched from the front line. Once launched the stack, the principes were moving to close gaps and form a solid front that prevented the enemy crept in among the Roman ranks.

Polibian legion (ca. 300-100 BC)

During the third and second centuries BC the Roman army remained a temporary popular militia. Every year, the Senate decided how many soldiers summoned and place of their destination. The armies were led by elected magistrates with imperium for a year: the consuls, who matched the most important military functions, and the praetors, who were engaged in the operations of lesser significance. At that time, each of the consuls had at his command a force of two legions.

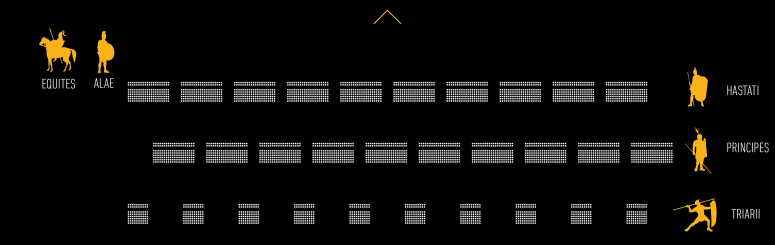

The characteristic legion consisted of 4,200 infants and 300 equites distributed in the following units:

Cavalry (equites): was originally the most prestigious unit and in which young Romans began to emphasize before beginning his political career. The equipment (horse, round shield, helmet, armor, sword and one or more javelins) was borne by each individual, but the state payed compensation if the horse died in battle. The cavalry was only about 300 riders divided into 10 turmae of 30 men. In command of ten men was one decurion.

Light infantry (velites): velites were basically harassing and javelin, but did not have a precise formal organization or a special role in the battlefield. Grouped the ancient accensi and rorarii, forming a contingent of 1,200 men. In training, they were located before the heavy infantry maniples, at 400 per line. In combat, they all gathered in front of the battle and after the release of their weapons, withdrew in an orderly manner to the third line alongside triarii.

Heavy infantry: was the main unit of the legion. It consisted of Roman citizens who could afford their own equipment: bronze helmet, shield, armor, short spear (pilum) and short sword (gladius). In the experience of the legionaries, it was organized in three lines:

- hastati: legionaries were younger and who formed the first line. They were armed with two pila of different weights, so that one had more scope and other pierce the enemies' shields. In the melee, they used the sword. As armor was common to use bronze plates fastened with leather straps that covered the heart and chest. They also used bronze helmet and scutum (long Roman shield).

- principes: legionaries were aged between 25 and 35, they formed the second line. They were armed as hastati but instead of wearing the chest plate they weare armor (lorica).

- triarii: the were veteran legionaries. They were located on the third line and went into battle only in extreme situations.

The first two lines of combat (hastati and principes) were divided into ten maniples, each of which divided into two centuries of 60 men led by a centurion.

The third line (triarii), was also divided into ten maniples of two centuries each, but only 30 men per century.

Every century had its own banner. In battle, the maniples were commonly arranged in a grid formation called quincux, so that the maniples of principes covered the open spaces left by hastati, being those covered in turn by triarii maniples.

Cohortal legion (from 100 BC)

At the end of the second century BC, Gaius Marius reforms introduced important changes in the army: these reforms responded to the need to create a new military scheme to defend the Roman territory after the serious losses suffered in the wars against Germanic tribes between years 106 and 105 BC. These losses, along with the progressive disinterest by the army of the wealthier classes, caused the shortage of men available for combat and, over time, the disappearance of the link between economic strength and military service. The changes were implemented in three points:

I. Recruitment: Mario instituted a new plant professional army, recruited from the poorest social classes, hitherto exempt from military service. From this moment, the legionary became a professional soldier who received pay and the promise of economic improvement after being licensed, without neglecting the opportunities to make a fortune by looting campaign. The mob, who had little hope of increasing their status by other means, immediately began to join the new army in which he was preparing for a period of 25 years.

Thanks to this reform, Mario achieved two objectives: to recruit sufficient men in a period of crisis and external threats for Rome and hereinafter avoid the serious economic problem caused by the loss in the contentions of most of the Roman middle class (therefore the death of citizens as economic ruin, unable to look after their properties during campaigns).

II.- Military structure: with a standing army and weapons by the State, Mario could standardize the equipment of troops and maintain training his men throughout the year. This became the legions in combat units with a physical condition and standards of insurmountable discipline, unparalleled in the ancient world.

Meanwhile, this new situation involved a serious risk to the stability of the Republic since from the time the soldiers could become more loyal to their commander that Rome itself. Especially when some general armed and financed legions from his own pocket. Henceforth, the army became a decisive factor in Roman political life, as anyone who was won legions' support could use as a tool to gain power.

Mario reorganized the legions:

- He eliminated the division infantry in specialized sections (hastati, principes and triarii): from the reform, legionary infantry formed a homogeneous body of heavy infantry, without discrimination on grounds of age weapons or soldiers.

- He eliminated the cavalry and the contingent of velites, which was totally in disuse: both were replaced by specialized auxiliaries troops, grouped according to their ethnic origin and conserving its peculiar style of battle.

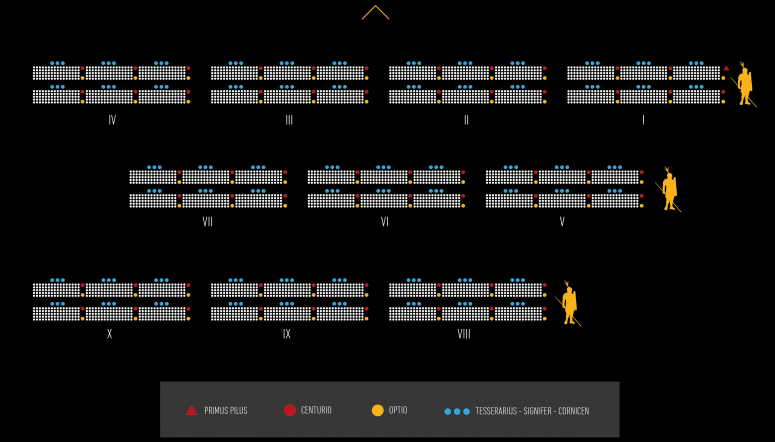

The new military system was based on the cohort as the basic unit. Each legion consisted of ten cohorts of 480 men; each cohort, three maniples of 160 and each maniple of two centuries of 80 individuals each, divided into ten units of eight soldiers (contubernia).

The centuries fought, marched and camped as a unit. As bringing in the weapons and all the other instruments and supplies for subsistence, the size of the supply caravans and fell and legions became much more rapid forces on the move. Meanwhile, the soldiers who formed the contubernia shared room (tent during the campaign), ate and lived together and created between them very strong bonds of solidarity.

A full legion consisted of about 6,000 men. Of the whole amount about 5,000 were soldiers and the rest non-combatant personnel. The military contingent was organized into ten cohorts divided into three lines of combat (acies triplex).

Since a legion consisted of ten cohorts, was bound to one of the three lines had a cohort more than the other two (usually the first) or that the three maniples were shared between the three lines of the tenth cohort on a one more in each.

Changes endowed the cohort of increased mobility is attributed to Caesar. Long before the reforms of Mario, the manipular cohorts were arranged in three lines of combat (hastati, principes and triarii). The innovations introduced by Caesar gave the cohort more flexibility to organize according to their needs in two, three or even four lines of combat.

As an independent unit it had a great ability to adapt to the demands of the enemy and the needs of the fight:

Changes endowed the cohort of increased mobility is attributed to Caesar. Long before the reforms of Mario, the manipular cohorts were arranged in three lines of combat (hastati, principes and triarii). The innovations introduced by Caesar gave the cohort more flexibility to organize according to their needs in two, three or even four lines of combat.

As an independent unit it had a great ability to adapt to the demands of the enemy and the needs of the fight:

- In the event of having few troops, the cohort could take acies duplex formation, keeping the same battlefront against an enemy superior in number and avoid being overtaken by the wings and defeated.

- Field with protected flanks, could adopt the formation of four lines to acquire deeper.

Since the mid-first century BC, the legions included devices artillery: each century was equipped with a crossbow mounted on a carriage (carroballista) and each cohort with a catapult, which not only increased the power of the legion in battle to open field, it also served to siege warfare.

Since August, the first cohort, which was always the best of the legion, had a century less but double of soldiers that the other (5 x 160 = 800).

The splitting of the first cohort could be extended to other: cohortes miliarias. The doubling of troops did not engage increasing the number of centuries but of soldiers, from every century to have a theoretical strength of 160 men.

During the Empire, the legions were often reinforced by allied troops (auxilia), composed of mercenaries with known military skill.

III.- Retirement: awarded troops with retirement benefits in the form of land. Proletarii ending the service received a pension and an estate in a conquered area to which they could retire.

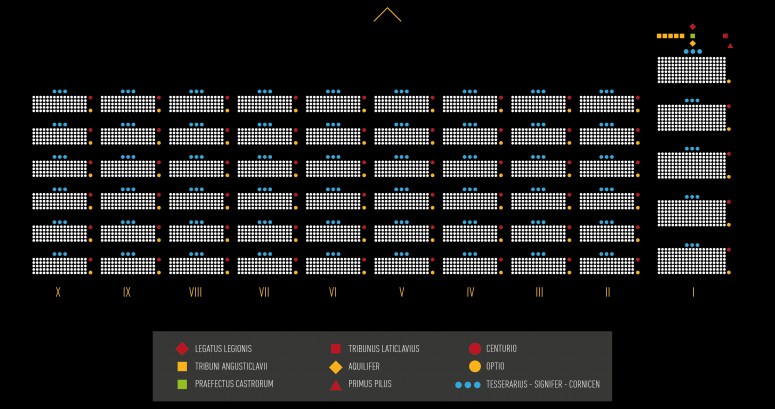

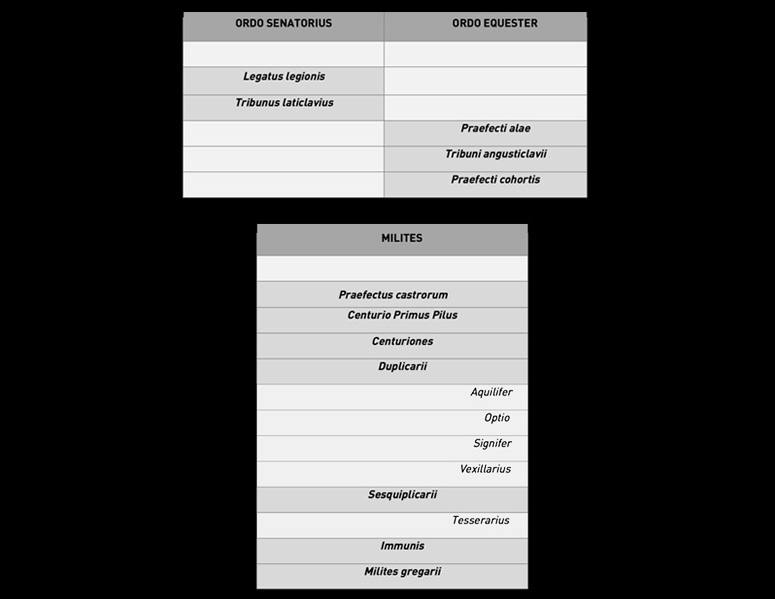

Organization

The legions were commanded by a legatus legionis. The legacy was chosen among the senatorial class of Rome and was the highest ranking military officer: used to be a former Praetor or a person of military talent. To be named legacy was necessary to obtain the approval of the Senate (senatus consultum), a proposal by a consul or a praetor. Were people of their utmost confidence and very often brothers or close relatives. Their number varied according to the importance of the campaign or extension of the province.

The legacy had no independent power of his general. Exceptionally, the legacy could lead the army independently if he had been invested with imperium: when a consul left the army or a proconsul his province, the legacy or one of the legacies took his place and was called legatus propraetore. In that case, the appointment could come to attribute command over several legions, but could only exercise outside Rome.

The legacy commanded for three or four years but could serve for a longer period.

In the provinces with only one legion, the legacy was also the provincial governor. But in the provinces with several legions, each legion had a legacy and the provincial governor had overall command over them all.

The legacy commanded for three or four years but could serve for a longer period.

In the provinces with only one legion, the legacy was also the provincial governor. But in the provinces with several legions, each legion had a legacy and the provincial governor had overall command over them all.

In imperial times, the Senate provinces were ruled by proconsuls or propraetors (the first had three legacies to their service and the second one). In the imperial provinces, the proconsul was appointed by the emperor among people who had previously been consul, praetor or senator and also had three legacies available.

In the first century BC appeared the free legacies, which were senators who were appointed legacies by the Senate for their particular travel to the provinces. They were formally legacies but had no role to play (legatio libera). Cicero wanted to end this practice without success and Julius Caesar limited the time to five years, continuing until the third century AD.

Subordinate officers were the tribunes, six in number for each legion: five regular officers and the sixth, a noble elected by the Senate: the tribunus laticlavus, which was created during the military reforms of Augustus and removed the middle the third century.

The office served basically for young senators who aspired to important posts in the scheme of the imperial state and that began their political career (cursus honorum) and take contact with the army. Usually it was exercised for one year.

In combat, their mission was to directly address the first two cohorts of the legion, the oldest and best managed and rarely entered the fray, while in the camp should coordinate with the praefectus castrorum to supply his legion.

In case of absence or death of the legacy, the tribune laticlavius replaced him assuming the title of tribunus laticlavus pro legatus.

The office of tribunus laticlavus did not exist in the legions stationed in Egypt where, being personal property of the emperor, Augustus had banned from the senators.

Also held the rank of officer the praefectus castrorum, a kind of field commander directly dependent the legacy and the tribunus laticlavius. His mission was to organize the camp of the legion and monitor the supply of the unit. In combat, he was in charge of commanding the legionary artillery. The charge was offered to soldiers who had been promoted on merit through the various ranks of a legion up to the primus pilus.

The primus pilus, was the highest rank centurion of the legion and belonged to the centurion of the first century of the first cohort. It was also the highest rank that an enlisted man could achieve in the Roman army after the reforms of Mario, which should remain in long rows, demonstrate courage and wisdom and be able to properly exercise leadership over their soldiers.

He was a soldier who acted as adviser of the legacy for his experience, participating in staff meetings and had under him the other centurions and all the soldiers of the legion.

The position of centurio primus pilus exercised for one year, after which they were licensed and entered in the equestrian order, as Roman knights. This gave them the right to participate in the life of the urban community in which were installed and aspire to the equestrian cursus honorum or to settle in Rome and advise directly to the emperor and his generals.

Only exceptionally they remained in the army in the rare range of primus pilus bis, as well as praefectus castrorum of the Legion.

After the primus pilus were the other centurions who managed the tactical command of each century. The most experienced (primi ordines) were part of the first cohort. They were assisted by an optio, a signifer (bearer and treasurer of the century) and a tesserarius (responsible for providing passwords and acting as liaison officer). Underneath, was the entire troop of legionnaires (milites).

After several years of service, the legionnaires were promoted from miles to inmunis, who were paid the same salary but were exempt from the general routines of the other soldiers. However, the first ascent itself became a soldier in principal, who distinguished between those who received pay and a half (sesquiplicarii), as tesserarius, and those earning double pay (duplicarii), as signifer, vexillarius and optio.

Rank among the centurions:

- Centuria I: Pilus Prior

- Centuria II: Princeps Prior

- Centuria III: Hastatus Prior

- Centuria IV: Pilus Posterior

- Centuria V: Princeps Posterior

- Centuria VI: Hastatus Posterior

As an exception, from the first century AD, the first cohort had a special status due to being divided into only five centuries:

- Centuria I: Primus Pilus

- Century II: Princeps

- Century III: Princeps Posterior

- Centuria IV: Hastatus

- Centuria V: Rear Hastatus

The optio was the officer who assisted the centurion of each century or decurion of each turma of cavalry, who helped in tactics and in maintaining discipline and physical fitness of soldiers. He could be appointed by the centurion himself or be elected by his peers.

He was ranked among the milites principales and had duplicarius category, meaning it was lowered heavy tasks and earned double pay. He aspired to be appointed centurion, and when he had reached sufficient qualification received the title of optio ad spem ordinis.

Classes:

- Optio centuriae: lieutenant of each century.

- Optio candidatus: appointed by the commander of his unit to be promoted to a higher rank, usually centurion.

- Optio custodiarum: officer in charge of the guard.

- Optio equitum: the legionary cavalry sergeant.

- Optio fabricae: charged to repair weapons in his unit.

- Optio praetorii: charged of the headquarters of his unit.

- Optio speculatorum: led the soldiers in charge of exploration and military espionage.

- Optio stratorum: led the military police.

- Optio tribuni: tribunus militum assistant.

- Optio valetudinarii: led the hospital in his unit.

- Optio ad carcerem: managed the military prison.

- Optio carceris: officer in charge of the prison cells.

- Optio draconarius: oldest bearers from the sergeant.

- Optio navaliorum: officer of a warship.

On the battlefield, the centurion stood in the first row of the unit, next to signifer, while the optio stood at the rear, to avoid, if necessary, the disbanding of the troops and to ensure the relay between lines typical of the closed order used by the Roman army.

Uniform and arms

Tunic (tunica): consisted of two rectangular pieces of wool or linen, sewn by the shoulders and sides and open for the passage of arms and head. They could be with or without sleeves. She dressed very loose, fell to his knees and was girded with a belt (cingulum) from which hung a leather kilt with metallic appliques.

Sandals (caligae): cut from a single piece of hard leather, sewn behind and joined a thick leather sole reinforced with nails.

Layer (sagum / paenula): manufactured from a single piece of cloth, holding the shoulders with brooches or simply covered and buttoned ahead (sagum). It could also be used as a poncho with a central hole for the head (paenula).

Armor (lorica): could be of net (lorica hamata), scales (lorica squamata) or plates (lorica segmentaria).

Helmet (galea): was padded inside and had a belt reaching to the side flaps which is tied under the chin. The centurions wore on their helmets transverse ridges for identification.

Sword (gladius): was short, straight edge and between 40 and 50 cm blade.

Shield (scutum): was oval until it was replaced by a rectangular in times of Julius Caesar. The coat was made of strips of wood in three superimposed layers and glued, coated leather or felt, and metal reinforcements in the center and on the edges. He weighed between 6 and 10 and a half kilos, and had about one meter long and 80 cm wide.

Javelin (pilum): consisted of a iron shaft about 60 cm with pyramidal tip and flat tail that fit into a slot in the wooden handle and was attached with rivets. In total, measuring about two meters and was designed to be thrown and to be nailed on the shield enemy, preventing it could be handled and also preventing could be reused by the adversary.

During the campaign Aquae Sextiae, Mario improved pilum giving it a weak bond between the metal shaft and wooden handle. This union was broken after the impact, so that, once released, no enemy could catch it and throw it against the Romans themselves. In addition, after the battle, the soldiers themselves could collect a pilum match and easily repaired.

Dagger (pugio): handgun with pointed blade about 25 cm in length.

Identification of the legions

The legions were identified by a number and a name. The numbers did not follow a uniform approach: Augustus numbered from number I which he personally founded, but also inherited and kept existing numbers; Vespasian respected the number of the legions who rebuilt from disbanded units; Trajan identified with the number XXX the legion he recruited first, since it already were 29 legions in service at the time of its founding.

Some end is unknown or is muted by Roman chroniclers, as they were very reserved when it comes to review facts of dishonorable or annihilated legions in the battlefield (damnatio memoriae). In fact, the numbers of the legions wiped out at the Battle of forest Teutoburg (XVII, XVIII and XIX) never were used again.

Since many legions shared the same number, it was necessary to distinguish them with a name, they could receive:

- as honorary title (Legio VIII Augusta)

- by feats of arms after winning a battle (Legio XX Valeria Victrix)

- for having remained faithful in a revolt (Legio XI Claudia Pia Fidelis)

- the region were concentrated (legio IV Macedonica)

- the place where it was recruited (Legio III Italica)

- by the merger of two or more legions (Legio XIII Gemina)

- for some special feature (Legio X Equestris)

During the last century of the Republic, the proconsuls who ruled the border provinces were becoming increasingly powerful. Command over legions fighting in distant and difficult military campaigns tended to shift the loyalty of those legions of the Senate to the person of the proconsul. These leaders (imperatores) began to confront each other, initiating successive civil wars for control of power (Sulla, Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Antony, Lepidus and Octavius). In this context, imperatores recruited a large number of legions without the authorization of the Senate, sometimes using their own resources.

When Octavian took power after defeating Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium (31 BC), he was found with 50 legions under his command. Octavian then decided to reorganize the army to which he disbanded some, others merged into one (geminae) keeping active a total of 28 to form the core of the first imperial army.

- I Germanica

- II Augusta (before Sabina)

- Pia Fidelis III Augusta

- III Gallica

- III Cyrenaica

- IV Macedonica

- IV Scythia

- V Alaudae

- V Macedonica

- VI Victrix

- Fidelis VI Ferrata

- VII Macedonica

- VIII Augusta Mutinensis

- IX Hispana (before Triumphalis)

- X Gemina (before Equestris)

- X Fretensis

- XI (Claudia Pia Fidelis from 42 AD, but the name that was previously unknown)

- Fulminata XII (formerly Antiqua)

- XIII Gemina Pia Fidelis

- XIV Gemina Martia Victrix

- XV Apollinaris

- XVI Gallica

- XVII (annihilated in 9 AD in the Teutoburg Forest before getting name)

- XVIII (annihilated in 9 AD in the Teutoburg Forest before getting name)

- XIX (annihilated in 9 AD in the Teutoburg Forest before getting name)

- XX Valeria Victrix

- XXI Rapax

- XXII Deiotariana

With the loss of the legions XVII, XVIII and XIX, the number dropped to 25 and Rome did not return to have 28 to 66 AD. (Claudius create the XV Primigenia and XXII Primigenia Pia Fidelis in 43 AD and Nero the Legio I Italica in 66 AD).

In 68 AD the Senate declared Nero persona non grata and accepted as emperor the governor Galba, who had marched from Hispania to Rome with a new legion, the VII Galbiana or Hispana. Two other generals opposed (Otto and Vitellius) and the struggle for power ended with the triumph of another general, Vespasian, the Flavian dynasty which established in 69 AD and ended the series of four emperors in one year. The conflict made essential a severe reform of the army, which set at 29 the total number of legions:

- XV Primigenia was dissolved.

- two new, the legio I Adiutrix Pia Fidelis and Legio II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis were formed.

- I Germanica and VII Galbiana joined to form the VII Gemina.

- and two more in favor of Vespasian from the beginning, were renamed: the IV Macedonica became IV Flavia Felix and XVI Gallica who was named XVI Flavia Firma.

Domitian created the Legio I Flavia Minervia (83 AD) and lost two: the V Alaudae (87 AD) and XXI Rapax (92 AD).

Trajan created other two: II Traiana Fortis and XXX Ulpia Victrix (102 AD).

Hadrian missed two: the IX Hispania (132 AD) and XXII Deiotariana (135 AD).

Marcus Aurelius created the legio II Italica Pia and the Legio III Italica Concors in 165 AD.

Septimius Severus created the legio I Parthica, II Parthica and III Parthica, and the total number of legions arrived to 33:

- I Adiutrix Pia Fidelis

- I Italica

- I Flavia Minervia

- I Parthica

- Pia Fidelis II Adiutrix

- II Augusta

- II Parthica

- II Italica Pia

- II Traiana Fortis

- Pia Fidelis III Augusta

- III Italica Concors

- III Cyrenaica

- III Gallicia

- III Parthica

- IV Flavia Felix

- IV Scythica

- V Macedonica

- VI Ferrata

- VI Victrix

- VII Claudia Pia Fidelis

- VII Gemina

- VIII Augusta Mutinensis

- X Fretensis

- X Gemina

- XI Claudia Pia Fidelis

- XII Fulminata

- XIII Gemina Pia Fidelis

- XIV Gemina Martia Victrix

- XV Apollinaris

- XVI Flavia Firma

- XX Valeria Victrix

- Primigenia XXII Pia Fidelis

- XXX Ulpia Victrix

Symbols

Since the reform of Mario, the aquila (eagle) was imposed as the legionary symbol par excellence. The eagles were held in precious metals and jealously guarded in the aedes signorum of the camp. The loss of the eagles was the greatest dishonor that the legion could suffer. The officer in charge of the eagle was the aquilifer.

Other banners:

- Signum: it was the proper standard of each century. It was topped by a spearhead or by hand and decorated with garlands and records likely identified the century and the cohort to which they belonged. His carrier was the signifer.

- Imago: during the empire, since the implementation of the imperial cult by Augustus, the legions carried a banner with the bust of the emperor. Chances are that accompany the legacy and the other officers. His carrier was the imaginifer.

- Vexillum: was a small banner of irregular detachments or units that provided services far from their legion (vexillationes). His carrier was the vexillarius.

- Draco: was a bronze animal head with open jaws, to which was added a tube, that produced a thud with the wind. His carrier was the draconarius.

Auxilia

Roman always trusted allied soldiers to complement their armies (auxilia). Usually they were recruited in the same place where the military campaign unfolded.

During the Republic, consular legions were accompanied by allied troops (alae sociorum) and horsemen (equites). The alae sociorum were troops extremely useful as additional soldiers, but above all, as military forces adapted to the terrain and conditions in the region where the battle was fought. Integrated by people of the allied nations, they were the same size of a legion and were placed between the consular legion and the Roman cavalry. The Republican cavalry was divided into 10 turmae of 30 men, each commanded by three decuriones at a rate of one for every 10 men.

Under Augustus the auxilia were a much more regular and professional force. They were also reduced in size: they ceased to be formations comparable to a legion (italics alae) and became units similar to a cohort, which made them more agile on the go, and its lower number of personnel regarding contingent Roman, less dangerous in case of revolt.

There were three types of auxiliary unit:

- The infantry was organized in cohors quingenarias (480 men) or miliarias (800), respectively distributed in six or ten centuries of 80 individuals.

- The cavalry was organized into units that were called alae. An ala quingenaria consisted of 512 men spread over 16 turmae of 32 men. An ala miliaria gathered 768 men in 32 turmae.

- Mixed units: probably have the same number of men that an ordinary cohort to which 120 equites (240 in miliarias) were added.

The legions dragged a lot of civilian personnel not directly related to the army: merchants, craftsmen, prostitutes (the legionnaires could not marry) which established around the permanent camps they created authentic cities.

The war at sea

During the early years of the Republic, Rome had no need to develop warships since the enemies against whom until then had struggled had been their neighbors italians and the conflict was settled out land.

In 282 BC the Roman ships suffered a major loss to the fleet of Taranto and later, in 265 BC, his ships came into conflict with the Carthaginian fleet in Sicily in what would be the eve of the First Punic War.

Aware of the naval superiority cataginesa and the effect would represent a victory at sea, in 261 BC the Republic began a program of naval development and simultaneously ordered the construction of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes to confront and destroy the hegemony of Carthage.

Tactics:

- Onslaught: warship all available metal spur on the bow located at the waterline or slightly raised below. Its function was to drill the wooden hull of the enemy ship and open a waterway. It was typical of fast boats and good maneuverability.

- Boarding: required approach and support, establishing an access bridge of the ship enemy to capture it and take its control. Require larger boats and a larger contingent of troops to subdue the enemy.

Given the greater experience Carthaginian naval battle, the Romans committed their victories to the infighting of the legionaries carried on board and corvus, a technical innovation that Punic strategists never got to neutralize. Corvus was a gateway attached to a mast at one end that presented at the bottom of another pike of metal: when the distance to the enemy ship permitted, he dropped the high end and the sink of metal dug into the helmet, allowing the legionaries start boarding and capture the ship.

At the end of the Second Punic War, Rome was consolidated as a maritime power and assumed full naval hegemony in the Mediterranean.