Imperatorial

It is generally accepted that the beginning of the end of the Republic took place when about 65 BC conspiracy of Catiline was found to abolish the established order and appointed dictator.

However, with the name of pre-imperial or imperatorial stage is designated the period of time between the civil war that began Caesar and Pompey in 49 BC and the appointment of Octavian as Imperator Caesar Augustus in 27 BC.

After the death of Sulla, Caesar entered the Senate and during the following years he progressed in his political career until he reached the first consulship in 59 BC.

The consulate of Caesar prompted major political, economic and social changes, developing a comprehensive set of laws and promoting radical agrarian reforms with the aim of providing land to disadvantaged families. At the first meeting of the Senate, Caesar also tried to offer a generous reward according to Pompey's veterans.

Aware of the strong opposition of Cato and optimates, thought he could propose the adoption of its agrarian law directly before the elections, but without the Senate was risky and could ruin his political career.

To avoid risk, Caesar decided to respect the normal channels and, as a counterweight to the conservative opposition, tried to close alliances with influential people of Roman politics. The strategy was unveiled at the vote in the Senate. It did not surprise anyone that the first to speak on behalf of their veterans were Pompey; but it was a surprise the identity of the second person who supported the proposals of Caesar: Marcus Licinius Crassus.

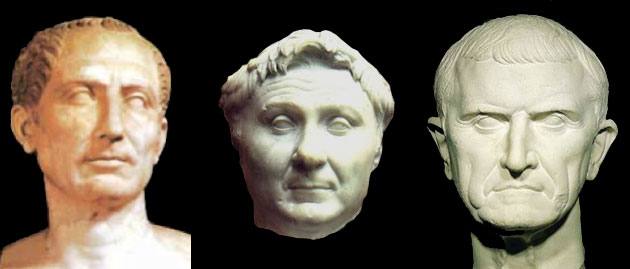

The First Triumvirate

Since then aware of what would become the First Triumvirate, an unofficial alliance of mutual aid granted by Gaius Iulius Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus to divide the higher positions of the Republic he had.

The reasons for this partnership are to be found in purely personal interests of each:

- Pompey needed Caesar to approve the agrarian laws for the benefit of its veterans;

- Crassus wanted a proconsular command to provide him the glory he had not succeeded in suppressing the revolt of Spartacus;

- Caesar needed the prestige of Pompey and Crassus funds to get the government of a province.

The agreement lasted until 53 BC and was reinforced by the marriage of Pompey to Iulia Caesaris, Caesar's only daughter.

After a difficult year as consul, Caesar received proconsular powers to govern for five years the provinces of Gaul Transalpina and Illyricum, thanks to the support of the other two members of the triumvirate, who met their commitments. In those two provinces was added after Gaul Cisalpina, after the sudden death of his governor, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer.

During the first year in office had to deal with several Helvetii and Germans invasions, who sought to occupy northern Italy. They were defeated in quick campaigns. Those raids advised Caesar to organize the province and prepare for his defense was insufficient and with the excuse to end skirmishes neighbors and the need for resources to pay fabulous sums owed, began the conquest of all Gaul.

Among his legacies were his cousins Lucius Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, Marcus Licinius Crassus, son of triunvir, Titus Labienus, Pompey's cliente, and Quintus Tullius Cicero, the youngest brother of Marco, all men who would be important in the following years.

César achieved countless victories, with which all Rome marveled. His legions crossed the Rhine twice to punish the Germans and twice sailed to raid Britannia. With these achievements attracted the attention of the people and Rome was inundated with treasures and slaves captured in war and looting.

That fact was not lost on the Senate, which observed with fear how Caesar gained popularity while amassing a personal fortune. Correspondingly, the achievements of Caesar in Gaul threatened the reputation and influence of Pompey in Rome itself.

But despite its successes and benefits accounted for Rome's conquest of Gaul, Caesar remained unpopular among optimates, who feared his ambition.

The optimates, led by Cato, criticized some of the laws of Caesar, underestimate their achievements and accused him of committing crimes against the Republic, especially for recruiting cams and have continued the war without the approval of the Senate.

Given this situation, which threatened his proconsulate and personal safety, Caesar called a meeting with his two allies. As he could not go to Rome without giving up their imperium, the meeting was held in the city of Lucca, on the border between Italy and Gaul Cisalpina in april 56 BC. It was attended not only the triumvirs but about two hundred senators and among all agreed that both Pompey and Crassus consulate would be presented the following year and, once consuls, would promote a law that extended five years the Caesar's proconsulate (Convention of Lucca).

The agreement prevented Caesar remain at the mercy of his enemies in Rome and in return, the extension gave him time to accumulate power and influence with a view to the consular elections of 49.

With the support of Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus were elected consuls in 55 BC and received extraordinary proconsular imperium: Pompey in Hispania and Crassus in Syria (leges Trebonia et Licinia). Then, both corresponded to the agreement and granted Caesar a five-year extension as proconsul in Gaul (lex Pompeia Licinia).

Cesarean strategy was intended to keep the political center to those who were his colleagues, but actually also top political rivals.

While Crassus was leaving to East for military glory, Pompey chose to delegate the government of Hispania their legacies and stay in Rome to seek support and recruit troops to face the return of Caesar.

The renovated in Lucca triumvirate soon weakened: first, the distancing of Caesar and Pompey and the other, with the death of Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae (53 BC).

One of the people that accentuated the rift was Publius Clodius Pulcher, a character who had rendered great services to the triumvirs but which, in turn, had become a de facto power to keep in mind. Clodius had organized bands of hitmen who often used to intimidate and coerce their opposites, to bust feedback and even for murder.

The triumvirate had tried to neutralize the power of optimates and Clodius had used for their purposes. Rome was plunged into uncertainty and more when optimates own responded to similar attacks led by Titus Annius Milo Papiano.

However, the ambitions of Clodius advised him away with Pompey, for which he used all kinds of tactics, from legal, supporting Crassus, until intimidating pretending Pompey there was a plot against him by men determined to kill him. This course of action suggested to Pompey actually was Crassus who financed Clodius and wanted to kill him, which in practice amounted to doubt their alliance.

The triumvirate was disintegrating, what also helped the death of Julia, daughter of Caesar and wife of Pompey, and his marriage with Metella, daughter of Metellus Scipio, one of the optimates leaders and bitter enemy of Caesar.

In a scenario of these characteristics, the Conservatives took the opportunity to attract gradually Pompey and murdering Clodius, took control of the streets (52 BC).

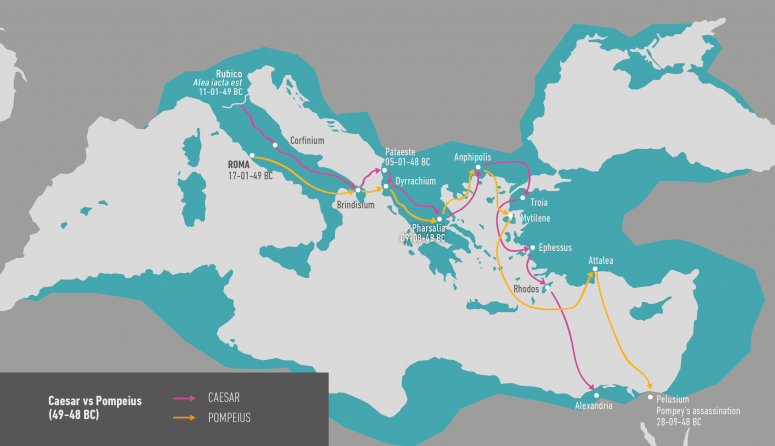

BEGINNING OF THE WAR

In 52 BC, positioned and clearly beside the optimates and being consul again with Q. Caecilius Metelus Pius Scipio, Pompey demanded that Caesar abandoned his command the following spring with what still missing months for elections to the consulate, there would be time more than enough to judge.

However, in the elections for tribune of the plebs was elected Curio, who revealed cesarean and use his tribunitia potestas vetoed all attempts to divert government Caesar in Gaul.

At the end of 50 BC Caesar encamped in Ravenna with the Legio XIII Gemina. Meanwhile, Pompey moved two legions at Capua and began recruiting cam illegally, an act that took the cesarianos in his favor.

Caesar was informed of the situation and sent a letter to the Senate where declared was a friend of peace and, after a long list of his deeds, proposed that he and Pompey renounce their control.

The letter was read on January 1, 49 BC by Marco Antonio, who replaced Curio in the office of tribune. The Senate did not consider the message and put the dilemma of Caesar disband his legions or be declared public enemy, so he understood that, choose the option he chooses, be in the hands of his political enemies.

The motion shall be immediately put to the vote and only two senators opposed: Curio and Celio. Marco Antonio, as tribune, vetoed and prevented were to be binding.

After Marco Antonio's veto to the motion that forced Caesar to leave his post as governor of Gaul, Pompey notified unable to ensure the safety of dissidents and above this, Antonio, Celio and Curio were forced to leave Rome disguised slave.

On January 7, the Senate proclaimed a state of emergency and exceptional powers granted Pompey, naming him consul sine colleague.

As Caesar received the news, he ordered that a small contingent of troops cross the border to the south.

At dusk the Legio XIII Gemina advanced to the Rubicon, natural border between Italy and Gaul, and gave his legionaries the order to advance (alea iacta est).

THE RUBICO

Caesar began his march and easily took different cities on the Adriatic coast. Immediately the news reached Rome, and with them, waves of refugees which in turn caused multitudes of people leave the city and an atmosphere of terror was common. Confidence in Pompey collapsed within days and senators who had relied on his quick victory over Caesar accused him of having brought the Republic to disaster.

Without knowing that Caesar was advancing with only one legion, Pompey gave Rome up for lost and ordered to evacuate the Senate, declaring traitors to the Republic to all magistrates to stay in the city.

The Senate began to consider the unthinkable: become out of Rome for the first time in its history, but such a decision could be interpreted as a sign of weakness that would give Caesar's legitimacy and trust.

Leaving Rome, the Senate betrayed those that could not afford to pack up and leave their homes and the feeling of belonging to the Republic was seriously damaged. The Republic became an abstraction: the annual elections, the vitality of the streets and public spaces of Rome, everything that shaped and defined the Republic was gone.

Caesar waited a few days the arrival of four other legions of Gaul and began the pursuit of Pompey and the Senate. On February 1 marched on Osimo and defeated Accio Varo, who recruited soldiers for Pompey. In turn, he tried to concentrate their troops in Brindisi, where chartered boats hastily trying to escape to Greece.

In Corfinium was the new governor of Gaul, Domitius Ahenobarbus, who hated equally Caesar and Pompey. Domitius was ordered to march with his men to the south, but disobeying the instructions of Pompey, tried to contain Caesar and became strong in the city of Corfinium, the same as the Italians rebels had become the capital forty years ago.

After the Social War, the people of Corfinium had obtained citizenship but were still very present memories of that struggle. For most of the Italian Republic meant little and identified more with popular ideas, considering Gaius Marius, Caesar's uncle, their reference.

On February 13, Caesar crossed the river Pescara and besieged Corfinium, which surrendered after a few days. Domitius was brought before Caesar by his own officers and begged to be killed, but Caesar refused and set him free. Corfinium not suffered any damage and cams novice became part of the army of Caesar. What seemed like a simple gesture of clemency, meant a great humiliation and a statement of purpose. There would be no lists of banned or massacres such as occurred in times of Sulla: enemies be forgiven only surrender. This allowed most of the undecided were relieved. Offered the image of who served well to their cause, avoiding any popular uprising against the caesarians.

After leaving Rome, Pompey went to Brindisi with the intention of moving to Greece and the East, where he had countless resources to deal with Caesar.

The February 20 Pompey moved half of his army across the Adriatic but the other half was trapped in the city, under the command of Pompey, awaiting the return of the fleet.

After defeating Domitius Ahenobarbus, Caesar arrived in Brindisi and ordered to build a dam to block access by sea. With the work still unfinished, the Pompeian fleet had time to go back and enter port. At dusk, Pompey kicked off the rest of the fleet and began full evacuation of Brindisi. Caesar, alerted by his supporters within the city, ordered take the assault, but it was too late and the boats were able to leave the narrow bottleneck that had been left open the siege works.

After the flight of Pompey, Caesar had to make a choice: pursue him to Greece, leaving his unguarded back and exposed to an attack by the Pompeian legions established in Hispania; or go to Hispania to secure his rear, allowing Pompey reorganize their forces from Greece.

After lean toward the latter, Caesar entered Rome on March 29, named Marco Antonio head of his troops in Italy and summoned the few senators who were to demand emergency funds that had been created to cover the costs of an eventual invasion of the Gauls.

Caesar remained in the city for two weeks, he reorganized the political institutions, decided on the basic issues and appointed praetor Marcus Lepidus. He then ordered to invade Sicily and Sardinia to protect the routes and supplies of wheat and left to Hispania, where there was still active Pompeian legions and a good number of clients and officers loyal to the cause of Pompey, the result of their long campaigns in that province.

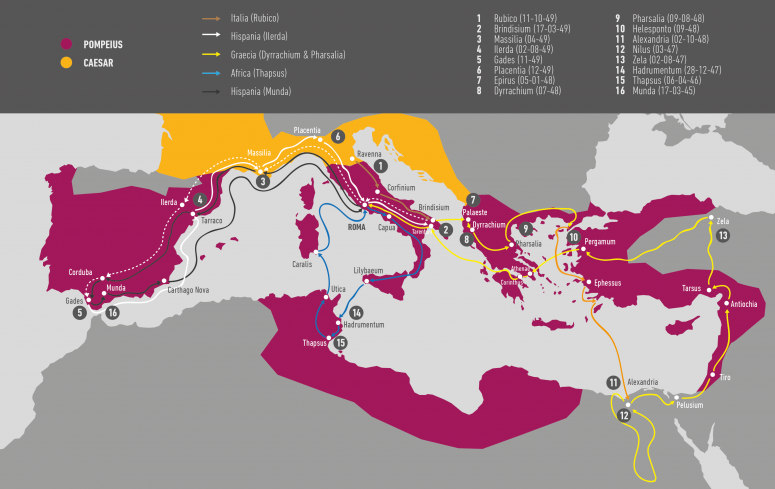

WAR IN HISPANIA.

The Pompeian armies were commanded by the legacies Lucius Afranius, Marcus Petreius and Marcus Terentius Varro.

Caesar concentrated nine of his legions and over 6,000 equites near Massalia, which was under the control of the proconsul of Gaul Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus who, after being pardoned by Caesar in Corfinium and have recruited a new army closed the doors from one city to the arrival of Caesar for the second time.

Caesar ordered his legacies Gaius Trebonius and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus who besieged the city and, without wasting time, went with the rest of the troops to Hispania Citerior to strengthen the three legions were sent there before.

Those three legions had contained the Pompeian troops within Hispania and maintained control of the main passes of the Pyrenees. With the arrival of reinforcements, the Caesarian army entered into the province and since mid-March camped near Ilerda.

The confrontation with the Pompeian troops fought in the summer of 49 BC, Caesar achieving victory on August 2 of that year. Soon after, Massalia surrendered and from there, after learning that he had been appointed dictator, left for Rome, he renounced and went back to Brindisi.

WAR IN GREECE.

Intending to sail to Greece in search of Pompey, Caesar concentrated his army in Brindisi. It consisted of a total of 12 legions and 1,000 cavalry, although many of them did not meet the number of theoretical effective, battered by recent campaigns in Gaul and Hispania.

Caesar had ordered the construction of numerous vessels, but before completion and despite the bad winter weather, on January 4, 48 BC embarked all possible men and sailed with a total of 7 legions and 500 equites. Marco Antonio and Aulus Gabinius remained in Brindisi along with the rest of troops and supplies awaiting the return of the fleet.

The Pompeian army commanded by Marcus Bibulus had naval superiority, with about 300 ships scattered throughout the southern Adriatic watching places of a possible enemy landing. Caesar, however, did successfully a day after setting sail on a beach far from major cities in the region, 150 kilometers south of Dyrrhachium.

Caesar began the occupation of the nearby coastal places, ensuring naval ports from which prepare for the arrival of the legions of Italy. The Pompeian squadron, warned, was put to sea, intercepted Caesarean fleet and captured 30 ships. Caesar, meanwhile, headed north, took Oricus and Apollonia and began the march towards Dyrrhachium. The news of the landing of Caesar surprised Pompey way of Macedonia, where he planned to recruit troops and deciding on the fly, ordered addressed in a hurry to Dyrrhachium. He entered the city shortly before Caesar arrived and pitched his camp on the north bank of Semani River in the town of Kuci, against Caesar, to be installed on the south bank.

Pompey's fleet began a tight blockade on enemy positions, anchoring near the coast and preventing the arrival of reinforcements. Meanwhile, the Pompeian squadrons of Illyricum and Achaia, led by Marcus Octavius and Lucius Scribonius Libo and supported by the Dalmatians, besieged Salona, capital of the province of Illyria ruled by Caesar. Proponents rejected the site with a surprise attack and forced the Pompeian to re-embark and run. Marco Octavian resigned to take Salona and joined Pompey in Dyrrhachium.

Come the good weather, sea conditions improved and in late February Marco Antonio crossed the Adriatic to meet the growing demands of Caesar, who demanded reinforcements.

The day of sailing, the fleet was spotted by Caesar and Pompey but a strong southwest wind pushed north from where both had established their camps. Marco Antonio disembarked with 4 legions and 500 equites and, after various tactical moves, joined Caesar's forces in the town of Scampi.

After the failure for failing to prevent the union of the enemy forces, Pompey entrenched and started a war of attrition.

Caesar sent Domitius Calvin to Macedonia with 2 legions and 500 equites to face Metellus Scipio, who moved from Thessaloniki to join Pompey.

A few days after the departure of these detachments, Pompey captured Caesarean fleet in Oricus naval base and continued to the base where Marco Antonio had left transport and burned it. Thus the cesarians viewed destroyed entire fleet in Greece and were no vessel to communicate with Italy.

In this situation, Caesar decided to give battle but was defeated on July 10 at the Battle of Dyrrhachium. However, the victory of Pompey did not help to stop Caesar, who escaped with their almost intact army pending better chance.

In a situation of total isolation, without floating without supplies, Pompey planned to harass the enemy and force him to surrender for lack of food. Meanwhile, Caesar fled south, away from Pompey, for supplies to stock up.

Pompey decided to march against Domicio in Macedonia, who had initiated the getaway to Thessaly to join the army of Caesar. By failing to intercept, Pompey then decided to head Larissa where he would meet with Scipio to form an army superior in number to cesarean.

Between 4 and 5 August, 48 BC, Caesar stopped his army at Pharsalia with the unique ability to fight.

It is possible that Pompey did not wish to fight the battle of Pharsalia, relying on the delay and the precarious situation of Caesar. However, the two armies met on August 9 and Caesar won a landslide victory.

After the battle of Pharsalia, the defeated managed to flee: Pompey left for Mytilene and then to Egypt; Metellus Scipio and Marcus Porcius Cato fled north Africa.

WAR IN THE EAST.

Pompey fled to the Aegean coast. There he chartered a boat to sail to Mytilene, where he hoped his wife Cornelia and his son Sextus Pompey. After meeting with them, they started with a small fleet heading to Egypt with the intention of seeking assistance from Ptolemy XIII, the young pharaoh of Egypt of just 12 years old.

A month after Pharsalus, Pompey reached the coast of Egypt. After spending a few days at anchor, the September 28 a small boat approached to Roman ships with the centurion Aquilas, soldiers and Septimius, a Roman former companion of Pompey, who feared the worst when he saw that there was any reception like those with which used to be received. Pompey was invited to come on board to take him to the beach, where was waiting Ptolemy XIII.

Once they have landed at Pelusium, Septimius drew his sword and pierced Pompey, who then was stabbed repeatedly by the others. Cornelia and the rest of the crew of the small fleet watched helplessly events from the sea. Pompey's body was decapitated and his body left on the beach, was rescued and incinerated by a veteran of the first campaigns of Pompey along with one of his freedmen.

Already in 47 BC, Caesar went to Egypt for Pompey with just 4,000 soldiers. There was surprised by the welcome offered to him by the Prime Minister of Ptolemy XIII, the eunuch Pothinus: the personal stamp and head of Pompey. Egypt was in civil war and King's advisors mistakenly believed that Caesar would be grateful and would support Ptolemy against his sister Cleopatra.

Knowing the outcome, Caesar burst into tears, so the death of a Roman consul, his old son in law and friend, and for having lost the opportunity to offer his forgiveness.

The Romans were trapped in Alexandria for a few unfavorable winds and Caesar began to bring order to the affairs of Egypt, doing and undoing at will. He settled with his troops in the royal palace, demanded exorbitant amounts of money and announced that arrange civil war between Ptolemy and his sister, which gave the order to disband the two armies at war and bring the two brothers him in Alexandria. Ptolemy XIII did not license to any soldier, but was convinced by Potino to keep the appointment of Caesar; meanwhile Cleopatra, who had blocked the routes to the capital, was isolated behind the lines of his brother.

One afternoon, a small merchant docked at berth palace. A lone trader charged a carpet that led to the presence of Caesar and, after unwinding, appeared unexpectedly Cleopatra herself, who would eventually seduce him.

Upon learning of the conquest of his sister, Ptolemy requested assistance through the streets of Alexandria and asked his subjects to attack the Romans. The mass responded enthusiastically and besieged the palace complex, Caesar was forced to recognize Ptolemy as set monarch with Cleopatra and returned Cyprus to Egypt. The situation worsened when the army of Ptolemy, about 20,000 men, joined the rioters, starting a battle for control of Egypt.

Over the next five months Caesar managed to resist the palace, seized control of the port, burned the Egyptian fleet and accidentally a store of books in port, failing in the attempt to control the Great Lighthouse. He executed the eunuch Pothinus and knocked up Cleopatra.

On November 9, the Egyptian troops commanded by general and former mercenary centurion Aquila, besieged Caesar in the royal palace and tried to capture the Roman ships in the harbor. Amid the fighting, flaming torches were released by order of Caesar against the Egyptian fleet, reducing it to ashes in a few hours. Although according to the version of Iulius Caesar himself in his Bellum Alexandrinum city was not hardly affected, other classical sources say that this fire would have spread to the stacks of the Great Library, which was in the neighborhood of Bruquion near the port.

On March 47 BC arrived roman reinforcements. Ptolemy fled Alexandria and it seems that, burdened by his golden armor, drowned in the Nile leaving Cleopatra with no rival to the throne.

Once restored communication lines, Caesar was informed of the new threats arise during his stay in Alexandria:

- Farnaces, son of Mithridates VI took advantage of the internal problems of Roma to expand their domains: he invaded Armenia, then part of the ancient kingdom of his father, the Ponto and part of Cappadocia.

- in Africa, Metellus Scipio and Marcus Porcius Cato were recruiting a powerful army.

- in Rome, the government of Mark Antony was creating mistrust.

Meanwhile, Caesar still remained two months in Egypt with his lover and then began the march towards Ponto to face Farnaces.

The battle took place in northern Cappadocia, near the city of Zela. The confrontation derived quickly in a Roman victory, completely annihilating the enemy forces (veni, vidi, vinci). Farnaces fled towards the Bosphorus and, with no power, was assassinated by an old rival.

WAR IN AFRICA.

The stay of Caesar in Egypt and subsequent march towards Ponto given time Metellus Scipio and Cato to form a new army in the province of Africa. Both managed to collect a total of 10 legions (about 50,000 men), reinforced by the allied troops of King Juba I of Numidia, which had 30,000 men and sixty war elephants.

After a short visit to Rome on December 28, 47 BC Caesar landed in the Punic city of Hadrumetum. The two factions were engaged in small skirmishes, since Caesar tried to postpone the direct confrontation awaiting reinforcements.

At one point at the request of Caesar, Boco II of Mauritania attacked Numidia and took its capital, Cirta, forcing Juba to leave the front and withdraw westward with his army.

After receiving reinforcements in February 46 BC and after the addition of two legions of defectors from the conservative faction, Caesar surrounded the city of Tapso and defeated Metellus Scipio and Cato, who committed suicide in Utica.

After the victory at Thapsus, Numidia became a Roman province. Defeated, Titus Labienus and the two brothers Gnaeus and Sextus Pompey escaped to Hispania.

Back in Rome, Caesar's victory gave enormous power and the Senate, shocked and intimidated, hastened to legitimize his victory naming him dictator for the third time by an unprecedented period of ten years.

In September, celebrated their triumphs and organized four consecutive ceremonies in which Gauls, Egyptian, Asian and African marched in chains before the crowd. The war between the Romans was masked by the victories against foreigners and the celebrations were unprecedented in size and in their duration. During the celebrations was executed Vercingetorix.

In the winter of 46 BC, exploded a new rebellion in Hispania led by the Pompey's sons.

Using the ancient influence of his father and resources of the province, Gnaeus and Sextus Pompey managed to collect 13 legions with the remains of army of Africa, the two legions of veterans of Pompey defeated in Ilerda, a legion of Roman citizens of Hispania and local mercenaries. At the end of 46 BC took control of most of Hispania Ulterior, including the Roman colonies of Italica and Corduba, the capital of the province.

Caesar's legates, Quintus Fabius Maximus and Quintus Pedius rejected direct confrontation, sought help and pitched in Obulco, thirty miles from Corduba.

Reinforcements arrived in December but conservatives, led by Sextus Pompey, avoided open fighting and took refuge in Corduba, so Caesar was forced to spend the winter in Hispania. To meet their needs for supplies, Caesar sacked the city of Ategua, circumstances which prompted a number of native Hispanics to leave Caesar and join the Conservatives.

Early in the spring of 45 BC, Pompey mobilized his army and prepared to face Caesar.

The two armies met on the plains of Munda, near Osuna, southern Hispania.

The battle began with no apparent advantage for either of the two contenders. At one point, Caesar took command of the right wing and the Legio X Equestris started forward. Realizing the maneuver, Pompey moved a legion of his right to reinforce the left wing, but when the Pompey's right flank was weakened, Caesar's cavalry launched a flank attack that would change the outcome of the battle.

At the same time, King Bogud of Mauritania, an ally of Caesar, attacked the Pompey's camp from the rear. Titus Labienus, the Pompeian cavalry commander, noticed the attack and moved to respond. However, Pompeian legionaries, subject to strong X Equestris attack down the left flank and cavalry on the right, mistakenly believed Labieno retired. Fearing the worst, the legionaries broke the front and fled.

Many Pompeian soldiers died during the withdrawal; others defending the city of Munda. Atio Varo and Titus Labienus were also killed, but Sextus and Gneus Pompey reached the city of Corduba, where they took refuge.

Caesar returned to Corduba March 18. Proponents, fearing that people join Caesarian troops set fire to the city. When Caesar arrived, the city was a heap of ruins and rubble. Given that scenario, he was unable to contain his soldiers who, furious at the lack of booty, massacred 22,000 citizens of all ages and auctioned survivors as slaves.

Gneus Pompey tried to flee with his fleet from Carteia but Caius Didius sailed from Gades and sank his galleys, forcing him back into the province. There was betrayed by indigenous and ended up being executed.

His brother Sextus Pompey managed to escape and take refuge in lands of laietani between Iberus river and the Pyrenees. He lived from theft to collect a sufficient number of followers to go to the Baetica and take control of Carteia and other cities in the area, which had the general support of the natives and the loyalty of veterans that his father had been established in the province.

During the month of June, Caesar met Octavio in Calpia, near present Alicante, returned with him to Rome and in September 15 secretly changed his will, taking in adoption his great-nephew and naming him his heir of all his properties.

Back in Rome, he took over as dictator but soon, under the pretext of defending the values of the Republic, was killed the Ides of March 44 BC by a conspiracy of senators led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus.

RETURN OF OCTAVIAN.

Caesar's death did not result in the expected return to normal that senators had hoped, but a new civil confrontation between his supporters and his murderers.

When Octavius came to Italy from Apollonia, he learned the contents of the will of Caesar and decided to fight to become the political heir of his great-uncle and beneficiary of two thirds of its assets.

Born under the name of Gaius Octavius Turinus, when adopted by Iulius Caesar (adoptio in hereditate), renamed Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (adoptees became part of agnatic adoptive family, although it was usual to retain their original surname adding the suffix -anus: Octavianus). In 27 BC the Senate awarded him the cognomen of Augustus and renamed Gaius Iulius Caesar Augustus.

Because of the various names that he held, is usually identified as Octavius during the period 63-44 BC, as Octavian between 44 and 27 BC and as Augustus after 27 BC.

After a warm reception by the soldiers of Caesar in Brindisium, Octavian demanded a portion of the funds had been allocated for his uncle to prepare for war against the Parthian Empire and set about strengthening his army.

In a later investigation into the disappearance of those funds, the Senate refused to take legal action against Octavian, since all that money had been used to increase his troops against Marco Antonio, the great enemy of the Senate.

In his march to Rome through Italy, status as heir of Caesar and funds that Octavian had acquired attracted many veterans of Caesar.

Meanwhile, Mark Antony had managed to expel from Rome Brutus, Cassius and most of the conspirators and had seized the power.

Octavian returned to Rome on May 6, 44 BC with the intention of asserting his title successor, but Mark Antony ignored him. When he arrived, Octavian found the consul Mark Antony in a fragile truce with the murderers of the dictator, who had granted amnesty on March 17.

But Mark Antony had lost the support of many caesarians, who did not accept their opposition to a motion to deify Caesar. Meanwhile, supporters of Caesar had moved towards Octavian, who was seen as a lesser evil and who hoped to use or manipulate in their efforts to get rid of Antony.

With the view of Roman increasingly against him and knowing his year of consular power came to an end, Antony tried to pass a series of laws that would grant control of Gaul, caesarean territory of Decimus Iunius Brutus Albinus.

Meanwhile, Octavian recruited a large army in Italy with veterans of Caesar and two legions of Antony, who had earned with the promise of significant economic rewards. In view of the military strength of Octavian, Antony saw the danger posed for him to remain in Rome and left for Gaul.

FIRST CONFLICT WITH MARK ANTONY.

After Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus refused to hand over Mark Antony the Gallia Cisalpina, he besieged him at Mutina. Decisions made by the Senate to stop violence were ignored by Mark Antony, knowing that the Senate lacked its own army with which to challenge him. This situation provided an opportunity for Octavian, who was appointed senator and received the imperium propraetore that legitimized so that, along with the consuls Hirtius and Pansa could succor Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus and overcome the siege.

In April, Mark Antony was defeated and forced to retreat. However, the two consuls were killed during the clashes, leaving Octavian as the sole commander of their armies.

After the victory, the Senate attempted to give the domain of consular legions to Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus but Octavian threatened not to cooperate in future offensives against Mark Antony.

In July, an embassy sent by Octavian came to Rome to demand that it be delivered the consulate left vacant after the deaths of Hirtius and Pansa and requested to rescind two important decisions:

- the decree that declared public enemy of Rome to Mark Antony,

- and amnesty granted to those responsibles for the death of Caesar.

When he met the refusal of the Senate, Octavian marched on Rome in command of eight legions. Without opposition, the August 19, 43 BC was elected consul with his family Quintus Paedius and Senate commissioned him to defeat Mark Antony, who still had 17 legions in Gaul.

However, because Octavian sensed that the Senate wanted to use him and because, meanwhile, Antony tried to approach Lepidus, another leading Caesarian, the three met secretly near Bologna and agreed they would face the senatorial party and would impose its decisions.

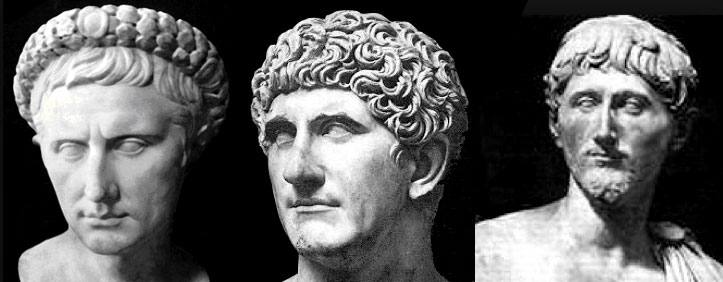

The Second Triumvirate

Octavian, Antony and Lepidus formed a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate or Triumviri Rei Publicae Constituendae Consulari Potestate (III VIR RPC), whose primary objective was to overcome the power vacuum caused by the assassination of Iulius Caesar. This alliance was agreed on November 11, 43 BC (agreement of Bologna), according to crystallize in a law passed by the popular assembly (Lex Titia) under which the triumvirs got special powers for a period of five years ( 43-38 BC).

This official agreement distinguishes the Second Triumvirate from the First, which went from not being a mere private political agreement between Gaius Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus to control the most important decisions of the institutions of the Republic.

The three commanders returned in triumph to Rome, where they put into practice some of his covenant: the principal members of the optimates should disappear from the political activity (proscriptiones). To do this, a list of 300 senators and 2,000 equites death row was published: the first on the list was none other than Marcus Tullius Cicero. The assets of the outlaws were distributed and supporters of Senate suffered a terrible blow, but still possessed a powerful army in Greece under the command of Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Thus began the so-called Third Civil War.

BATTLE OF PHILIPPI AND TERRITORIAL DIVISION.

On January 1, 42 BC the Senate deified Julius Caesar posthumously (divus Iulius), whereupon Octavian, as the adopted son, took the opportunity to run the son of god (divi filius).

Antony and Octavian sent 28 legions to Greece to face the armies of Brutus and Cassius, who had fixed there their bases. After two clashes, were victorious in Philippi and both Brutus and Cassius committed suicide.

The triumvirs reached a new territorial agreement for power sharing: Marco Antonio left Gaul, the provinces of Hispania and Italy in the hands of Octavian and in return, received the eastern part of the empire. Mark Antony traveled to Egypt and allied himself with Queen Cleopatra VII, who was the lover of Julius Caesar and mother of his illegitimate son, Caesarion. Lepidus kept the province of Africa.

Octavian had to decide which parts of Italy was to settle tens of thousands of veterans of the campaign in Macedonia, which the triumvirs had promised to fulfill from the beginning. In addition, tens of thousands who had fought on the republican side with Brutus and Cassius, who could easily ally with a political opponent of Octavian if they are not contented, also needed a place to settle. There was no more public land controlled by the government to be earmarked as a settlement for his soldiers, so Octavian had to choose between two options: face many Roman citizens because of the confiscation of their land or face the soldiers, which in turn could cause a lot of opposition against him in the heart of Rome.

Octavian chose the former: up to 18 Roman cities were affected by the new settlements, reaching some of its inhabitants to be expelled or at least partially evicted from their land.

While Octavian in Rome faced continued unrest and complaints from all sectors of the country, Mark Antony lived a luxurious and carefree life in Egypt rich with Queen Cleopatra.

At that time, Octavian filed for divorce from Clodia Pulchra (daughter of Fulvia and her first husband, Publius Clodius Pulcher) and decided to return her to her mother, who was the wife of Mark Antony.

Fulvia, insulted, formed an army with Lucio Antonio to join forces against Marco Antonio Octavian.

Lucio and his allies were besieged in Perusia and surrendered in early 40 BC. Fulvia was exiled to Sicyon and Lucio and his army were forgiven. However, Octavian showed ruthless toward political allies of Lucio and ordered to run them the March 15, anniversary of the assassination of Julius Caesar.

WAR WITH SEXTUS POMPEY.

Sextus Pompey had become a renegade general since the victory of Caesar on his father and on the Republican side.

However, the sudden death of Julius Caesar was for him a very welcome development: after successive victories that allowed him to dominate all the Baetica, he negotiated a truce with Lepidus, who was the governor of Hispania Citerior and Gaul Narbonense, and obtained authorization to go to Rome to receive the paternal inheritance, which he also added a significant amount of money the Senate awarded him compensation for the properties that had been confiscated from his father.

In 43 BC, at the proposal of Cicero, the Senate passed a laudatory decree in his honor, offered to nominate him for the position he had taken his father in the college of augurs and appointed commander of the Republican fleet with the title praefectus classis et orae maritimae.

In August of that year, Octavian controlled consulate proposal from his colleague Quintus Paedius imposed a law that bans were imposed on all murderers of Caesar (Lex Paedia de vi Caesaris interfectoribus). Although Sextus Pompey had no involvement in the incident, was included in the official lists.

The domain of the fleet ensured some security Sextus Pompey; but as the governors of the two Hispaniae and Gaul supported the triumvirate had no onshore no basis to give him security and rest. Sextus merely attacking coastal areas and increase their troops with those who had suffered the proscriptions and the multitude of slaves who adhered to him.

When were enough forces landed in Sicily and settled on the island headquarters, where controlled grain supplies to the city of Rome. After defeating Octavian in 42 BC off the coast of Escileo, Sextus was at the height of his power calling himself the son of Neptune (Neptuni filius).

Given the role that Sextus Pompey had succeeded, both Antonio and Octavian competed to consolidate an alliance with him, although ironically was a member of the Republican opposition party to cesarean faction.

Octavian got a short-lived alliance when he married Escribonia the daughter of Lucius Scribonius Libo (father of Pompey) and had with her a daughter, Julia Major. However, when not even a year had passed since the wedding, Octavian asked for a divorce to marry Livia Drusilla.

Meanwhile, in Egypt, Antony began an affair with Cleopatra, conceiving with her three children (Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus).

Aware of his deteriorating relationship with Octavian, Antony left Cleopatra in 40 BC and sailed with a large number of soldiers to face Octavian in Italy.

However, two developments allowed the triumvirs will achieve a certain approach: the death of the wife of Antony and rebellion of the troops, who refused to fight.

In the autumn of 40 BC, Octavian and Antony approved the Treaty of Brindisi by which Lepidus would remain in Africa, Antonio East and Octavian in the West. The Italian peninsula was accessible to all for the recruitment of soldiers, although in reality, this provision was useless for Antonio from the East. To further consolidate its alliance with Antony, Octavian offered in marriage to his sister, Octavia, with whom he had two daughters (Antonia Major and Antonia Minor).

Sextus Pompey, who had gained control of the sea, threatened Octavian to refuse shipments of grain through the Mediterranean and to cause widespread famine in Italy.

In 39 BC, it was agreed temporary peace with the Treaty of Misenum: blocking of Italy would be lifted once Octavian granted Sextus Pompey the territories of Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily and Peloponnese, also assuring the consulate to 35 BC.

However, the territorial agreement between the triumvirs and Sextus Pompey fell apart: first, Octavian divorced Scribonia and married Livia Drusilla (38 BC); otherwise, one of Pompey's naval commanders betrayed him returning control of Corsica and Sardinia to Octavian.

To attack Sextus Pompey, Octavian needed support to Antony, who had tried to maintain good relations (he forgave his brother Lucius Antonius and gave his sister Octavia as wife) and proposed a new agreement to extend the Second Triumvirate five years.

Antony agreed to support him against Sextus Pompey, but in return, asked for help to start a campaign against the Parthians, as a revenge for the defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC.

At a meeting in Taranto, Antony gave 120 boats that were used against Sextus Pompey, while Octavian offered 20,000 legionaries to help Antony against the Parthians.

However, Octavian sent only a tenth of the promised, which was considered by Antony as a provocation.

Octavian and Lepidus launched a joint operation against Sextus Pompeius in Sicily in 36 BC. Despite some setbacks Octavian, general Agrippa managed to destroy almost completely Pompey's fleet at the Battle of Naulochus.

Sextus Pompey fled to East with what remained of his troops, but the next year would be captured and executed in Miletus by one of the Antony's generals.

Lepidus and Octavian regrouped Sextus Pompey's defeated troops, but Lepidus felt with sufficient authority to claim Sicily for himself. The war seemed inevitable but the soldiers did not trust Lepidus and Octavian will soon convince some of the legions that were passed to his side. Finally, Lepidus surrendered and, although he was allowed to retain the office of pontifex maximus, was expelled from the Triumvirate. Abandoned by all, Sicily and Africa lost the benefit of Octavian, saw finished his public career and went into exile.

Octavian had secured his position and began to prepare the political and military strategy for their impending break with Mark Antony.

WAR WITH MARK ANTONY.

The vast Roman territory became a matter of just two: Antony and Octavian.

While Mark Antony dealt with the reorganization of Egypt, Octavian was engaged in the development of agricultural activity and the integration of the Western Roman provinces.

Antony campaign against the Parthians ended in disaster.

Moreover, as Cleopatra had the capacity to reorganize its army and since he was engaged emotionally with her, Mark Antony decided to send Octavia back to Rome.

Octavian took the decision to attack Antony, noting that the Romans rejecting legitimate wife in favor of a lover of the East, the general was becoming less and less Roman. Master of political propaganda, Octavian extended in Rome a review of all adverse Cleopatra. He also attacked Mark Antony, whom he accused of having ambitions to reduce the prominence of Roma in the region.

When Octavian again assumed the consulate on January 1, 33 BC, opened the first session of the Senate with a vehement attack on the concessions of titles and territories offered by Antony to his family and his queen (after the conquest of Armenia in 34 BC Antony named his son Alexander Helios as governor of the territory). The senators were confused: some came out in defense of Antony while others sided with Octavian. Among his acolytes, Lucius Munatius Plancus and Marcus Titius provided Octavian the information he needed to reaffirm before the Senate all the accusations he had made against Antony. After storming the shrine of the Vestal, Octavian obtained the testament of Mark Antony and saw how it bequeathed to his sons territories under Roman rule for them to govern them as kingdoms.

The document was read to the plebs and because of that the Senate revoked the powers of Antony as consul and declared war on the regime of Cleopatra in Egypt.

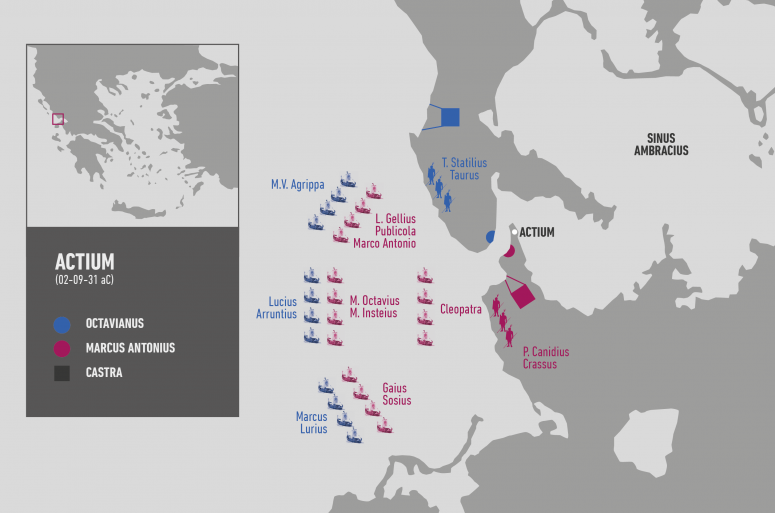

Early in 31 BC, while Antony and Cleopatra were temporarily stationed in Greece, the fleet of Octavian, led by Agrippa, managed to transport troops across the Adriatic. While Agrippa blocking shipping lanes used by Cleopatra and Antony to the supply lines, Octavian landed just opposite the island of Corcyra (Corfu) and marched south. Trapped both by sea and by land, the army of Antony began to desert. In a desperate attempt to free the naval blockade, the fleet of Antony led by Gaius Sosius and Lucius Gellius Publicola put to sea through the Bay of Actium, where he was intercepted by Agrippa on September 2, 31 BC.

Antony and part of his naval forces were saved only by the intervention of the fleet of Cleopatra, who had remained near there as a last resort in the event of a defeat.

Octavian did not give up and gave chase. After another victory in Alexandria on August 1, 30 BC, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide: Antony fell on his sword in the arms of Cleopatra, as she stopped by a poisonous snake bite.

Having used his position as Caesar's heir, Octavian was well aware of the risks that would allow another had a chance to share the same path so, after commenting that "two Caesars are too many," he ordered Caesarion, the son of Iulius Caesar and Cleopatra, was killed.

After this victory, the Republic annexed the rich lands of Egypt. Nevertheless, the new territory was not included in the regular system of government of the provinces, but was converted into personal property of the emperor and, as such, property transmissible to his successors.

In 27 BC the Senate awarded Octavian the title of Imperator Caesar Augustus.

Octavian secured his power by maintaining a balance between the republican appearance and the reality of a dynastic monarchy with constitutional aspect (Principality): in principle, Octavian shared functions with the Senate, but de facto power Princeps was complete. He never formally accepted the absolute power although in practice it exercised, assuring his power with several important posts of the Republic and keeping the knob on several legions. Octavian was renamed Augustus and became the first emperor of Rome.

Imperatorial coinage

The coins minted during that period represent the transition between the republican and imperial coins series of Augustus and his successors.

In the first phase (49-45 BC), coins incorporated the names of the characters fighting for power, but not their portraits. These emissions coexisted with those of traditional Republican era and were a propaganda tool in the hands of Caesar and his successors, who controlled the Capitoline mint from almost the beginning of the Civil War until the closed Augustus in 40 BC.

The turning point came in January of 44 BC, when Caesar took the unprecedented decision to play his own portrait in the coins. His murder came just three months later, but that breakthrough innovation immediately became a rule, paving the way for imperial emissions.

In the post-Caesar phase (44-27 BC), emissions from Republicans, particularly those of the tyrannicides Brutus and Cassius, and the Triumvirate (Mark Antony, Octavian and Lepidus) are distinguished. After the battle of Philippi (42 BC autumn), only Mark Antony and Octavian continued to fight for absolute power in Rome. The issue was finally resolved in the battle of Actium (31 BC) and the subsequent fall of the Kingdom of Egypt, the last bastion of Mark Antony, during the following year (30 BC).

For these reasons, the pre-imperial coinages are usually divided into four groups:

- Emissions of Pompey the Great, his sons and supporters.

- Emissions of Julius Caesar.

- Tyrannicides emissions and their supporters.

- Triunvirs emissions and their supporters.

Do not forget that between 49 and 40 BC, these coins, minted mainly in military mobile workshops, coexisted with republican emissions of the Capitolina mint, whence also came, between 43 and 41 BC, a significant number of pieces of gold.