The Social War

Background: Italic peoples

Latins were one of the many ethnic groups that arrived in Italy during the second millennium BC.

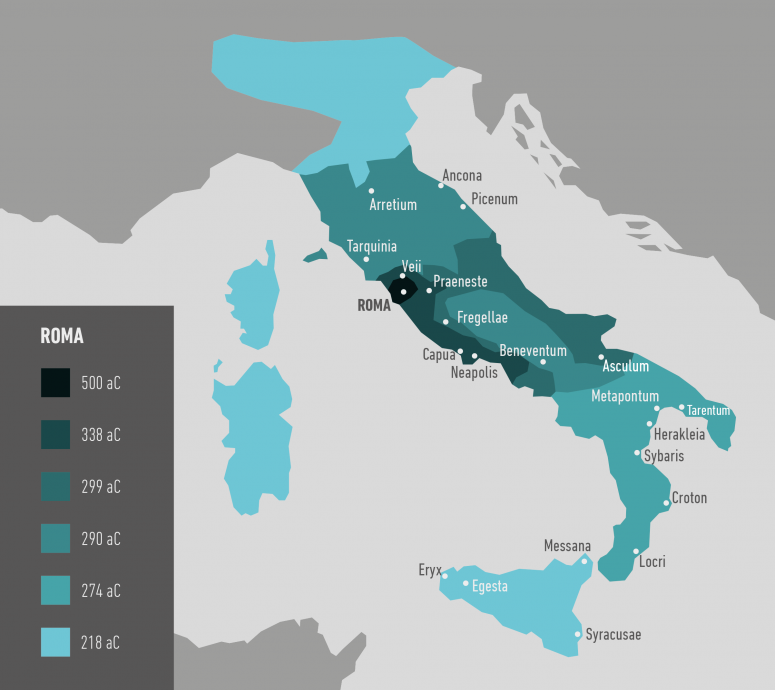

Ancient Rome was originally a village that settled in the coastal strip between the lower reaches of the Tiber and the Gulf of Policastro. From the initial settlement area, Latins withdrew to control only the region of Latium Vetus, bounded by the rivers Tiber and Trerus by the Volscians and Praenestinian mountains and the Tyrrhenian Sea.

It was an ethnic minority not only in central Italy but even in the same Latium but, nevertheless, went on to become the unifying axis of all the peoples of the peninsula.

The development of Rome and Latium began during the Etruscan period. After the fall of the monarchy (the last three kings of Rome were Etruscans), Latins won in Ariccia (506 BC) and Rome thwarted the expansionist aspirations of Etruria, while retaining the republican government that had recently been established. The withdrawal of the Etruscans north of the Tiber and soon after the severe defeat suffered against Syracuse in the naval battle of Cumae (474 BC), they caused Etruria lost its power condition in the central Mediterranean.

With the disappearance of the Etruscan supremacy, frequent fights broke out over ownership of the land between Rome and other cities in the region, which defeated at the Battle of Lake Regilo (496 BC). Rome imposed its hegemony with Foedus Cassianum (493 BC), an alliance signed with the Latin League (the confederation that had created the villages and Latin tribes to ensure their mutual defense) by which the Roman and Latin armies unite to ensure protection of italic tribes, the spoils of war would be divided, would promote joint colonies in the conquered territories and establish among the citizens of Rome and Latin populations of a community of rights.

This treaty further strengthened the position of Rome, adding the army of the Republic still weak military power of its neighbors. Nevertheless, the alliance was not enough to establish a climate of confidence and cities of Latium repeatedly tried to get rid of the superiority of Rome and abusive covenants imposed on them.

Before getting to dominate the entire region of Latium, Rome had to deal with a sudden war. In the early fourth century BC, a gallic expedition crossed the Apennines and headed for Rome. Terrorizing and destroying everything in their path, the Gauls were intercepted near the Alia river, where they defeated the Roman army and continued their advance until the city of Rome (387 BC).

Survivors fled to Rome overcome by panic and with the population took refuge on the Capitoline hill. The rest of the city was looted and destroyed. Probably not be ready for a siege and the appearance of an outbreak, it was agreed by the Romans agreed to pay a heavy compensation.

The agreed end of clashes with the Gauls and the parenthesis of calm after the early stages of the war in Latium (Latin Wars was not completed until 338 BC, after the First War Samnita) they not accounted for Rome consolidate period of peace. With the growing power of the Republic, which already controlled the whole territory of Latium, the Samnites opposed the strength of the emerging power: the Samnite Wars and struggles against Pyrrhus of Epirus Rome kept wrapped in continuous conflict.

The Samnites wars

For reasons that are not known with certainty, Praeneste denounced the Foedus Cassianum and supported by volscos, ecuos, faliscos, etruscans and rose again in arms against Rome (383 BC). Despite the shortage of Roman forces, praenestinos were derotados and some allied cities were absorbed by the Roman Republic (381 BC).

Roman victories continued to occur, but the Republic had turned against many of those who had hitherto been their allies in the fight against their common enemies. The most important cities of Latium (Praeneste, Tibur) finished losing their freedom, so they repeatedly arms against Rome; other important towns like Tusculum, which had been severely punished, came to his aid: only left side Roma localities as Norba and Signia and a small number of villages under minor.

First Samnite War (343-341 BC). Samnita Rome and the Federation clashed for control of the northern Campania. As a result of an alliance between Rome and Capua, the Samnites latter besieged population but they were repelled by Rome. The Romans defeated in the battles of Monte Gauro (342 BC) and Suessula (341 BC), but had to withdraw from the war before ending the conflict due to the revolt of several of its former allies in the Second Latin War. Although the confrontation did not lead to anything definite, he allowed the Romans to interfere in the internal affairs of a rich and populated area and take Capua, the largest and most prosperous city in the region, center of a dense network of trade relations with other cities. As a result, they happened to be in the orbit of Rome.

Concerned about this new phase of Roman expansion to the south, Latins decided to intervene and with the support of some cities bells again faced Rome (340 BC). Latin-bells forces were defeated and decimated by the Romans in the battle of Vesuvius (339 BC) and Trifanum (338 BC), which ended the Latin Wars.

From that moment, the cities of Latium ceased to exist as autonomous political entities and its history is confused with that of Rome.

Second Samnite War (327-302 BC). The samnites interpreted as casus belli the support that Rome gave the city of Neapolis, threatened by the Samnites, as Fregellae fortification, which until then had defined the border between the two peoples (328 BC). If at first the Romans tried to fence off the Samnite territory in 321 BC the Samnites captured the entire Roman army at the Caudine Forks.

After disarming all the soldiers and their commanders, the Romans were subjected to humiliating conditions: they could only save the life after lean one by one before the Samnites.

In 316 BC Rome resumed hostilities, but was again defeated at the Battle of Lautulae (315 BC).

After building the Via Appia, which connected Rome with Capua, and as they established colonies along its route in order to lock up samnitas within its territory, the Romans defeated the Etruscans (samnitas allies since 311 BC ) at the battle of Lake Vadimo (310 BC).

Finally, after breaking through Apulia, the Romans took Bovianum, the Samnite capital.

The end of the war was to control Rome and Campania waiver by the League samnita all territorial expansion.

Third Samnite War (299-290 BC). To face Roma, the Samnites allied with Etruscans, Sabines, lucans, Umbrians and the Gallic tribes of northern Italy. Roma won victories separately against all of them and reoccupied Bovianum (298 BC) to completely defeat at the Battle of Sentinum (295 BC). As a result of its surrender in 290 BC, the Samnites were subjected to Rome and left clear for concentrate its efforts on the southern Italian peninsula road.

Either way, the Samnites continued to resist Roman rule and allied themselves with the enemies of Rome whenever they had the opportunity, first with Pyrrhus of Epirus during the Pyrrhic War; then with Hannibal during the Second Punic War and later with other Latin peoples in the revolt known as the Social War.

The Pyrrhic wars

With the intention of responding to the belligerence of Rome, which had declared war, the city of Tarentum sent an embassy to Pyrrhus of Epirus to beg him to cross the Ionian Sea and defend them against Romans (281 BC). To persuade him, was at their disposal a large contingent of soldiers and collaboration of all peoples of southern Italy.

Pyrrhus traveled to Tarentum in 280 BC and although he had not yet received the promised reinforcements, attacked the Romans with their own troops and those of Tarentum.

He ordered his army between the cities of Pandosia and Heraclea and defeated the Roman consular army, commanded by Publius Valerius Levino. Pyrrhus' victory caused a number of casualties and brought significant consequences: the allies of Pyrrhus, who until then had been kept at a safe distance, they joined the king and even several subjects of Rome abandoned their cause. He managed to win Brutius, Lucanians and Samnites. But his victory was costly and the experience of the last battle showed the difficulties that could meet its goal of conquering Rome.

Aware of this difficulty, sent his minister Cineas to Rome with proposals of peace, as he gathered the forces of its allies and slowly marched towards central Italy. Back, Cineas Pyrrhus did know he could not wait any results through diplomatic channels and, consequently, the king decided to continue the war. He moved to Rome, pillaging the lands of the Roman allies in their way. He was only 35 km from Rome, so a new day's march would have led to the walls of the city. At that time it was reported that Rome had made peace with the Etruscans and the other consul, Tiberius Coruncanius, had returned with his army to the city. With the news Pyrrhus slowed his progress and gave up hope when agreeing to peace with the Romans, then he decided to slowly back to Campania, retire to their winter quarters in Tarentum and stop the war.

Clashes resumed the following year in Apulia, waged the final battle in Asculum (279 BC). The first meeting took place in an area where the unequal nature of the terrain complicated movements of the phalanx and gave advantage to the Romans; however, Pyrrhus maneuvered to lead his enemies to level ground and Romans were defeated. Nevertheless, this victory gave no advantage to Pyrrhus, who was forced to retreat back to Tarentum to overwinter.

He then received two embassies from Syracuse.

The city was defenseless before a Punic invasion and, after a long civil war, the generals of the two warring sides sought the support of Pyrrhus.

This company seemed simpler than the one in which was shipped but required before suspend hostilities with the Romans, who also wanted rid of so uncomfortable to complete the occupation of southern Italy without interruption adversary.

Since both contenders shared common desires, they reached an agreement to suspend the war.

From Syracuse Pyrrhus returned to Italy in the autumn of 276 BC. He recovered Locri, who had gone over to the Romans, but the battle of Beneventum in 274 BC represented the end of the military career of Pyrrhus in Italy and had to return to Epirus.

The Second Punic war

After the wear of the First Punic War (264-241 BC), the Carthaginians had not only suffered serious economic losses but had to accept a costly conditions of surrender.

To improve its ailing economy, Carthage turned his gaze to the Iberian Peninsula in order to find an alternative to the resources that had provided the territories of Sicily and Sardinia, lost the benefit of Rome.

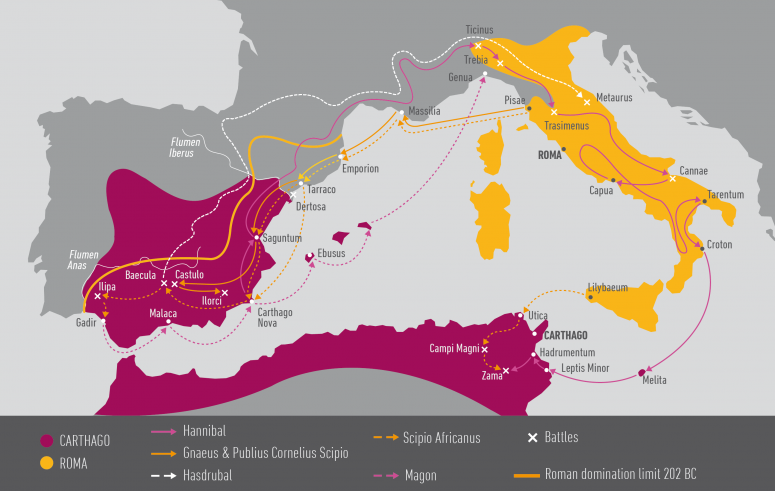

The expedition was led by Amilcar Barca, and then by his son Hasdrubal the Handsome who commanded the army, founded Qart Hadasht (Carthago Nova), established alliances with the tribes of the southeastern peninsula and undertook military action to control the hinterlands of Central Plateau. At his death (221 BC), it was succeeded by Hannibal Barca, who continued deployment until the Battle of the Tajo (220 BC). With the victory, the Carthaginians secured the rear before embarking on his expedition against Rome and getting a good number of prisoners of war and grain reserves for supplies.

The clashes started between turbolitani, allies of Carthage, and Saguntum, located in the Phoenician influence limits but allied of Rome, were the prelude to a war that followed the Carthaginian conquest of that city (219 BC). After eight months of siege without help arrived from Rome, which had prioritized control a revolt in Illyria, Saguntum did not resist.

In the plans of Hannibal, the conquest of Saguntum was essential: the city was one of the most heavily fortified in the region and it was risky to leave it under Roman control. Hannibal also expected to remain his army satisfied with the sacking and get enough to keep track of Rome loot.

Carthaginian departed Iberia with an army of 100,000 men and, after crossing the Gallia Narbonensis and cross the Alps in mid-fall, arrived in northern Italy in the spring of 218 BC.

Scipio tried to attack, but a detachment of Numidian horsemen commanded Maharbal rejected them in a skirmish on the banks of river Ticinus. Scipio, who saved the life thanks to the courage of his 17 year old son (who would later known as Scipio Africanus), retreated to Placentia to defend the passage of the Po River. Hannibal crossed the river and offered him into battle. Understanding the superiority of the Carthaginian cavalry Scipio refused battle and decided to retire across the Trebia River, a tributary of the Po, waiting for the second consular army commanded by Tiberius Sempronius Longus. Against the advice of Scipio, Tiberius Sempronius Longus imposed his judgment and ordered into combat. The Carthaginians defeated and victory, Hannibal took control of northern Italy.

The following year, the consul Gaius Flaminius, the Romans ambushed the Carthaginian army. Hannibal was informed of Roman positions and avoided going through a marshland that guaranteed a direct march to Rome. The consul, surprised by the decision, was forced to chase him and confronted Hannibal in Lake Trasimenus, where the Roman troops were encircled and defeated again. Despite the victory and the request of his generals, Hannibal, who had lost vision in one eye, decided not to besiege the city of Rome and chose to weaken the resistance Roman destroying his army again and again. To do this, he went to southern Italy in the hope of inciting a rebellion among the Greek cities of southern and gather more financial resources to defeat the Romans.

Meanwhile, Fabius Maximus was named dictator. One of his first decisions was to change military strategy: ordered avoiding direct confrontations and, instead, concentrate all efforts on cutting the supply line of Hannibal.

The following year he was replaced by the consuls Paulus Emilius and Terentius Varro, who recruited a large army to confront Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC).

Hannibal allowed his troops back from the center, U-shaped bending over and taking advantage of their riders were superior to the Roman cavalry, forcing the latter to retreat and in a clever maneuver surrounded the legions to annihilate them completely.

Over the next three years they joined the Carthaginian cause the cities of Capua, Syracuse and Tarentum. In addition, Hannibal achieved an alliance with King Philip V of Macedon (217 BC) which caused the start of the First Macedonian War.

In Rome, he panicked and Romans began to appreciate the tactics of Fabio, who was reelected consul in 215 and 214 BC.

Sardinia

The Romans had been at loggerheads for years with the people of Sardinia. In 216 BC, the only legion stationed on the island had been decimated by disease and the army was financed with taxes that fell on the native population. Discontent caused the population to request aid to Carthage, who sent an officer with orders to finance the revolt. Hasdrubal the Bald was appointed commander of this mission and in 215 BC landed on the island, where he was defeated by the Romans in the Battle of Cornus.

Sicily

In 212 BC, Syracuse decided to break the treaty of alliance with Rome and Carthage to side. The Carthaginians promised to cede control of all Sicily in exchange for help to defeat Rome. The Romans declared war and sent the consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus with four legions and a fleet. The inability of the Carthaginians to bring aid to Siracusa brought down the city and allowed the Romans to restore and expand its dominance in Sicily and, thus, have an enormous source of supply of cereal.

Iberia

After the battle of Dertosa (215 BC), the Romans had secured their settlements north of the Ebro River. From then strove for the loyalty of the Iberian tribes and enter gradually into Carthaginian territory south of the river.

Unlike Gnaeus and Publius Scipio, who did not receive reinforcements from Rome due to the difficulties that the Republic was having on its territory by the pressure of Hannibal, Hasdrubal had received two new armies, commanded by his brother Mago and Hasdrubal Gisco.

Gnaeus and Publius Scipio had managed to persuade the king of Numidia, Syphax, to initiate hostilities against Carthage (213 BC). However, stability in the Iberian Peninsula allowed Hasdrubal to travel to Africa to quell the rebellion and return to Iberia in late 212 BC with another 3,000 numides under the command of Masinisa, which would be the future king of Numidia.

The Scipio brothers hired several thousands of celtiberian mercenaries and noting that the Carthaginian armies had dispersed and were settled in different places, planned to divide his forces and attack separately. With just days apart, Publius attacked Mago Barca near Castulo and Cneo attacked Hasdrubal Barca at the Battle of Ilorci (212 BC).

After the death of both, Rome realized that it was necessary to leave the Carthaginians in Iberia to avoid a new invasion of Rome.

The Republic entrusted the task to Scipio, the future Africanus, who already had 25 years of age. In 209 BC, taking advantage of the Carthaginians throughout south-eastern Iberia were scattered, he took Carthago Nova in a bold and brilliant strategic maneuver, defeated Hasdrubal in Baecula (208 BC) and then to Mago and Hasdrubal Gisco in the battle of Ilipa (206 BC), which would be decisive in the Carthaginian withdrawal of the Iberian peninsula.

Baecula. After the defeat of Baecula, Hasdrubal and the remains of his army went to Italy to meet with Hannibal.

In Italy, meanwhile, the Romans decided to take the initiative and sent a large army to besiege the city of Capua.

Hannibal forced the Romans to raise the siege, but could not stay in the city and had to leave for lack of supplies.

After Hannibal had retired, the Romans managed to besiege the city again. All Hannibal attacks to recover were repulsed. Hannibal then decided to go to Rome and lead to the withdrawal of the legions to defend the square, which indirectly also got the goal to lift the siege of Capua.

He arrived at the gates of the city, but the powerful fortifications and the presence there of four legions made him abandon the effort. In addition, the legions besieging Capua did not move from their positions, bringing the city finally could not resist and was taken by the Republic.

The fall of Capua facilitated Romans the reconquest of the main cities of southern Italy controlled by the Carthaginians, including Tarentum, which Fabius Maximus reduced to slavery many of its inhabitants.

When Hasdrubal came to Gaul, he tried to meet with Hannibal in the area of Umbria in central Italy. However, the post fell into the hands of the consul Claudius Nero, who at the time was fighting Hannibal in southern Italy. The Romans displaced southern part of the contingent commanded by Claudius Nero and met with consular legions north to command the other consul, Livius Salinator, reinforced with Praetor in Gaul, Lucius Porcius Licinius. Hasdrubal was defeated in the battle of Metauro, where he lost his life.

Learned of the death of his brother and the destruction of his army, Hannibal decided to abandon their positions in Lucania and Bruttium fall back on, in the south-western tip of the peninsula.

Ilipa. After Hasdrubal left for Italy, Scipio managed to attract to himself several Iberian tribes and repeatedly defeated the Carthaginians, who were concentrated in the Guadalquivir valley. The Battle of Ilipa (206 BC) marked the final expulsion of the Carthaginians from the Iberian Peninsula.

After the defeat, Hasdrubal Gisco returned to Africa and Magon gathered what remained of his troops in Gadir and left for the Balearic Islands (still under the control of Carthage), from where he continued to Genua to join the army deployed in Italy.

Magon disembarked in 205 BC and tried to help his brother Hannibal, but was defeated in 203 BC and died a few months later.

After the battle of Ilipa and those that followed, the Romans took forever of the last remaining Iberian cities under Carthaginian control.

Africa

The year after the conquest of Iberia, Scipio was elected consul (205 BC) and decided to directly attack the city of Cartago.

Once in Africa (204 BC), the Romans found an ally who would be decisive: Masinisa, nominal king of Eastern Numidia, stripped of his throne by Syphax, king of Western Numidia and ally of Carthage.

Scipio besieged Utica but was forced to retire because of the joint intervention of the armies of Syphax (numidian) and Hasdrubal Gisco (Carthaginians).

In the spring of 203 BC, the Romans began a new attack and managed to lay siege to the city of Utica for the second time. The Carthaginians and Numidians met their last reserves to face Scipio. Campi Magni battle ended with Roman victory, with the expulsion of the throne of Numidia Syphax and the start of peace negotiations with Carthage. Hannibal was required to return from Italy.

However, the arrival of the Carthaginian troops of Hannibal and Magon to Africa broke the agreement in principle and the war began again.

Scipio obtained the collaboration of Masinisa, which provided auxiliary troops and military support. Hannibal landed at Leptis Minor and both disputed victory in the Battle of Zama (202 BC) which represented the first great defeat of Hannibal in his military career.

Conditions imposed by Rome to Carthage:

1 loss of all possessions located outside the African continent;

2 prohibition to declare new wars without Rome's permission;

3 obligation to deliver all the military fleet;

4 Masinisa recognition as king of Numidia;

5 acceptance of borders between Numidia and Carthage that determines Masinisa;

6 payment of 10,000 talents of silver in 50 years (about 260,000 kg);

7 Maintenance of the Roman troops in Africa for three months;

8 delivers 100 hostages chosen by Scipio as a guarantee of compliance with the treaty.

Hannibal accepted the conditions and the treaty was ratified in 201 BC.

The Social War

The victory in the Samnite Wars allowed Rome to gain control of the entire peninsula. This domain is translated into a set of alliances between Rome and the Italic cities in more or less favorable conditions depending on whether the city had allied with Rome voluntarily or he had been subjected because of the defeat in the battlefield. These cities were theoretically independent, but in practice Rome had virtual control of its foreign policy and the right to demand payment of taxes and the contribution to the army of a certain number of soldiers (in the second century BC Italic peoples contributed a number of men that is usually set between half and two-thirds of the army).

If the period of the Second Punic War is excluded, during which Hannibal had limited success to seduce some Italian populations and address them to Rome, in general, most of them declined to subscribe to maintain the condition of customers in exchange for local autonomy.

However, the policies promoted by Roma in the field of land distribution resulted in a great inequality.

Some initiatives had tried to amend what the Italians considered an imbalance between their contribution to the military force of Rome and the concessions they received in exchange for the distribution of land and the acquisition of Roman citizenship.

These efforts reached their highest level with Marcus Livius Drusus (91 BC). His reforms had granted Roman citizenship to the allies and thus greater participation in the foreign policy of the Republic, but the response of the Roman senatorial elite proposals Druse was rejected and after his assassination, all of Italy tried to plead independent of Rome and war broke out.

Already in 95 BC, after years of relative peace, the approval of the Lex Licinia Mucia had caused a strong discontent among the Italians. Proposed by the consuls Lucius Licinius Crassus and Quintus Mucius Scaevola, the law represented a reaction to the fraudulent acquisition of Roman citizenship and returned to the legal regime applicable to them according to their origins to those deprived of it.

The revolt, called Marsica War or Social War, began in the autumn of 91 BC and was triggered the murder of Marcus Livius Drusus.

Elected tribune of the plebs in 92 BC, Drusus tried to adopt a series of populist measures that aggravated the confrontation: on one side, wanted to use the power of the people to return to the Senate its traditional role in Roman politics and at the same time, to the growing demands of the Italians, deploying all their energy to obtain stability commitments between these peoples and the Senate itself.

With the support of part of the senatorial class, Drusus began tribunate with several reforms, after which the purpose of joining efforts and find ways of hiding approach:

To curry favor popular, Drusus led to the lex Livia frumentaria which provided wheat distributions between the rabble at very low prices.

And to please the Italian peoples, citizens were promised that they faced in exchange for the cost of a new distribution of land. To do so, he developed an agrarian law, for which those peoples ceded territories of ager publicus occupied since the time of the Gracchi (mainly in Etruria and Umbria) and tried to pass the lex Livia de sociis that gave them Roman citizenship by way compensation to achieve stability.

But the extension of citizenship to the Italians (far outnumbered the Romans) would have meant a restructuring of institutions and the introduction of a series of administrative and political changes that could not be adopted without risk, so most Roman oligarchy rejected them and the law was not approved.

From that moment the tension soared and then when probably at the request of the Senate Drusus was murdered, war broke out.

Italics communities were incited to rebellion in the south, the Samnites, Lucanians, Hirpini, Frentani, Pompeian and Campanian, commanding which stood Gaius Papius Mutilus, the main promoter and organizer of the uprising; in the north the Marsi, Piceni, Vestini, Peligni and Marrucini, commanded by Quintus Silo Poppaedius. They also joined the cause much of the transpadanian Gauls, but not for long, Etruscans and Umbrians.

Commanders and officials allied contingent:

Titus was commander of Mársico Lafrenius group until his death in combat in 90 BC. He was succeeded by Fraucus, also died in combat action.

Titus Vettius Scato commanded the Paeligni until committed suicide in 88 BC.

Gaius Pontidius was head of the Vestini to 89 BC.

Asinius Herius Marrucini commanded until his death in 89 BC. He was succeeded by Obsidius, also died in combat.

Gaius Vidacilius commanded the Picentines until 89 BC, when he committed suicide.

Publius Praesentius probably led the Frentani.

Lucilius Numerius directed the Hirpini to 89 BC.

Lucius commanded the Pompeian Cluentius in 89 BC, when he was killed in action.

Titus Herenius probably led the Venusian throughout the war.

Trebatius could have commanded the Iapigios during the war.

Marcus Lamponius commanded the lucanos.

Marius Egnatius led the Samnites until his death in 88 BC. He was succeeded by Pontius Telesinus, who was also killed in action later that year.

The villages facing Rome and joined by the alliance (socii) declared independence, created their own senate and coined common currency. The new republic was called Italy and placed their capital in Corfinium east of Rome.

Asculum conflict began in the late 91 BC when, still recent murder of Drusus, the angry mob killed a Roman embassy led by Praetor Q. Servilius. Violence to all inhabitants of the Roman city extended.

The rebellion spread rapidly, encouraged by the attitude of the Roman Senate, shortly after the conflict began, passed the Lex Varia (90 BC), by creating a court of high treason to investigate the responsibilities of those who had led the Italians to the war and that, logically, were found among those who had been supporters of Drusus.

During the first phase of the war, various Roman defeats followed. To reverse the situation, in 90 BC, the Senate summoned Mario and placed in front of the armies of the North. Pompeius Strabo (father of Pompey the Great), acted in Piceno and L. Cornelius Sulla in Samnium.

Although brief, the war was devastating, both by the size of the opposing armies as the hardness of operations. The death toll was extremely high and many cities were destroyed.

The progress of the war only stopped when the Senate relented and approved the Lex Iulia de civitate (90 BC). This law was introduced by L. Iulius Caesar and granted Roman citizenship to the Italians who had remained faithful to Rome (the Latin colonies) and all those who had laid down their arms or lay down in a short time of time.

These concessions broke the unity of the Italian allies and, indeed, most of the rebels welcomed the measures.

Shortly thereafter, the Lex Plautia Papiria (89 BC) perfected the integration of new citizens, incorporating solutions technical-political and extending the right to citizenship to virtually all of the Italic peoples, the transpadanian Gauls and certain allies who had distinguished during the war.

Only samnitas left out, since continued to fight alone until the year 82 BC.

On that date, having come to the aid of Mario in his civil confrontation against Sulla, the Samnites were involved in a confrontation at the gates of Rome. Under the orders of Pontius Telesinus attacked the army of Sulla in the Collina Gate and after a tough battle, Sulla won victory simultaneously ending the Social War and the First Civil War of the Republic.

Of course, the resolution of problems involving the new situation, the process of political reorganization, the appointment of new charges, the adaptation of indigenous institutions to the Roman and the changes necessary to bring such different sensibilities, not achieved easily and they were only resolved in Italy in 49 BC by Julius Caesar.

Coinage: mints and legends

During the war, the Confederates peoples minted currency. Emissions were basically coinages in silver with similar size and weight to denarius.

They were the first to circulate copies of the Roman denarius, but gradually they got rid of that influence and eventually incorporating own original designs.

The main difference from the silver coins issued by the Senate is in the disappearance of the head of Roma on the obverse, which was replaced by the bust of Italy, emblem of the insurrectionists.

Most likely there was no central mint, as the legends of the new silver coins (some in Latin and others in Oscan) show plurality of emissions from different areas occupied by communities that formed the confederation.

Although there is no absolute certainty, it is generally accepted that the coins with oscan legend were coined in Bovianum and Aesernia, while silver coins with Latin legend were minted in Corfinium.