The Republic

The Republic (res publica populi romani) is the period of Roman history that extends from the end of the monarchy, after the expulsion of the last king Tarquinius Superbus (509 BC) to the beginning of the Empire, often set in 27 BC when the Senate gave Octavian the title of Imperator Caesar Augustus.

During the V century BC was established in Rome gentile state, aristocratic regime led by a small number of descendants of the oldest families in the city (gens).

Between the fourth and third centuries BC, Rome established itself as the dominant power and subdued the other peoples of the italic peninsula. During that period, decreased the differences between the patricians and plebeians heads and they all gathered around a ruling aristocracy, the nobilitas. With the proportional reduction in the number of patricians, the term plebs was used since then to designate the masses.

From the mid-third century BC, Rome began a long series of wars that led to dominate the entire Mediterranean world.

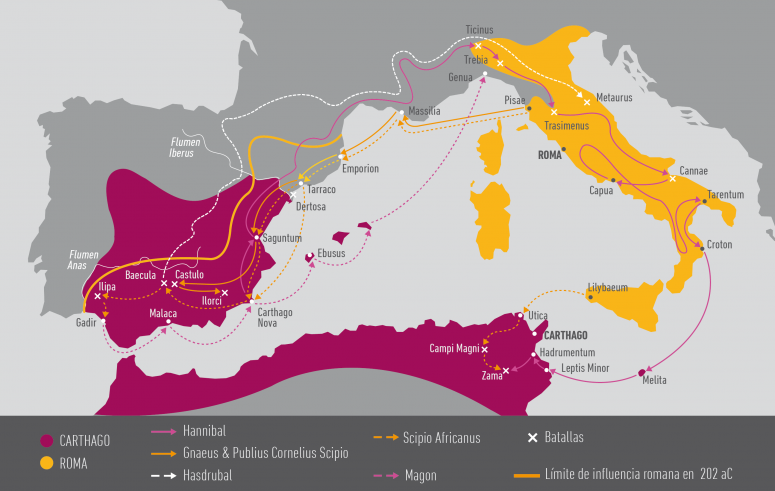

The Punic Wars marked the first stage of the Roman expansion.

The First Punic War (264-241 BC) was developed in Sicily and was the first of three major wars that took place between Rome and Carthage. The major powers of the moment fought continuously for 23 years for supremacy in the western Mediterranean.

In 264 BC, Rome took the Carthaginian colonies in Sicily and after years of battles of different signs, Carthage surrendered in 241 BC. After seizing Sicily, Rome took advantage of the weakness of his enemy to also occupy Corsica and Sardinia.

The Second Punic War (218-201 BC) was developed in Hispania, Italy and North Africa. After the military expedition across the Alps, Hannibal remained with his army in the peninsula for 16 years, defeating few legions confronted him to halt his advance. However, despite unquestionable victories like Cannae, the Carthaginian army was not able to undertake the siege of Rome, perhaps because the passage of the Alps and the subsequent battles he had meant losing a number of soldiers and war elephants. Meanwhile, the Republic was unable to expel him from Italy, overwhelmed by the many conflicts that had to cope simultaneously.

At the same time that Rome fought against the Carthaginians in Italy, Hispania and Sicily, also fought in Greece the First Macedonian War, which began in 214 BC following the approach that had occurred between Philip V of Macedonia and Hannibal himself. After the Roman victory in the Iberian Peninsula, the existing deadlock situation in Italy was finally resolved by sending several legions to Africa, aiming to besiege the city of Carthage. The severity of the threat forced Hannibal to return in a hurry, who was finally defeated at the Battle of Zama by Scipio, nicknamed since then Africanus. The defeat marked the end of the war and with it, Carthage lost all its trading colonies, leaving its possessions confined to the territory of the city itself.

The Third Punic War (149-146 BC) almost fell to the battle of Carthage, an operation siege that ended with the sacking and complete destruction of the city, Carthage was destroyed, exterminated or enslaved its population and its territory became the Roman province of Africa (146 BC).

After the wars with Carthage, Rome left its natural borders of the peninsula and submitted gradually new territory: it is successively confronted the Macedonian kings Philip V (197 BC) and Perseus (168 BC) and Antiochus III of Syria (189 BC).

In Hispania, consolidated its dominance with taking Numancia (133 BC) and in Gaul, the occupation of the southern territories, which have become the province Narbonense, allowed terrestrial union of Rome with the Iberian peninsula.

The conquests behaved real economic revolution. The booty, slaves, war reparations and taxes paid by the provinces, enriched Roma and individuals. These conquests also altered the fragile social balance of the Republic, the taste was introduced for luxury and institutions initially created to manage a city lost its usefulness in that great country.

During the period between the end of the second century BC and the first century BC, Rome obtained new military successes: Mario won the War of Jugurtha (105 BC); Sulla defeated Mithridates, King of Pontus (88-85 BC); Pompey submitted Syria (64 BC) and Judaea (63 BC), Caesar conquered Gaul (51 BC).

The vast territorial extension made new additions soon to become ungovernable areas for the Senate.

In addition, Roma experienced major political changes and significant social instability: the military victories became slaves in the largest social strata of the city, to the point of rebelling against Rome under the leadership of Spartacus and cause was called III Servile War or War of the Slaves (73 BC).

Moreover, the dimension of a growing army revealed the importance of having authority over the troops for political gain. So it was that emerged ambitious characters whose main goal was power, even at the cost of defying the authority of the Senate.

The conditions to reach the Empire and its foundation as a political system created during the civil wars that followed the death of Julius Caesar.

After the war he fought Pompey and the Senate, whom he defeated at Pharsalia (after defeat Pompeian army in Africa in Tapso and Hispania in Munda), Caesar was erected in absolute ruler of Rome and made himself Dictator perpetuus. This decision did not please the more conservative members of the Senate (optimates), who conspired against him and killed him in the Senate building itself during the Ides of March 44 BC.

Years later, the young Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, became de facto the first emperor of Rome after defeating in the battlefield, first to the murderers of Caesar himself, Brutus and Cassius at Philippi (42 BC) and later at Actium (31 BC) to his former ally Mark Antony, who had joined the queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt in an ambitious alliance to conquer Rome. A triumphant return from Egypt, since that moment become a Roman province, the implementation of the imperial political system over the domains of Rome became inevitable, and although initially maintained republican forms, reality soon became a dynastic monarchy character (the Principality).

Invested with the title of Imperator Caesar Augustus (27 BC), Octavian ensured its power with major reforms and promoted a political and cultural unity centered on the Mediterranean countries.

Main institutions of the Republic

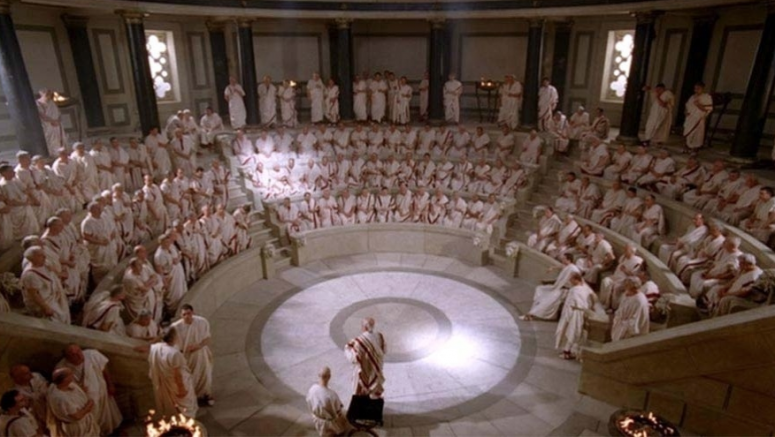

The Senate

The Senate was an essentially conservative institution with the men of the upper classes in whom the people deposited their confidence in the management of public affairs. It was meant to be consilium reipublicae sempiternum, but the advent of the Empire was a shift of the functions of the camera at the Princeps. Due the Senate lost his essence and was reduced to a resigned institution to obey designs of the emperor.

During the Monarchy, there was a Council of Elders (Senatus) that sought to counterbalance the Royal Institution.

Born as an advisory and control institution, consisted initially only by citizens patricians, representatives of 30 families from Rome, at the rate of one appointed by each gens. Exceptionally, when a senator died the king was empowered to appoint a temporary substitute (until the appointment of a substitute for the gens itself). The custom of royal appointment ended up giving the king the election of senators. The office of senator had for life. As the number of gens was unchanged (30), was also unchanged the number of 30 senators (the successive families always arose from a common trunk and therefore integrated into any existing gens).

During the early years of the Republic the Senate had 300 members, all patricians. They could access citizens who have the status of pater familias and those who have held curule magistracies (consuls, praetors and aediles).

However, as citizens entitled to a seat in the Senate came to be insufficient to cover the losses that occurred through death or exclusion and the number of senators could not be less than 300, with time the censors had a free choice between all citizens, even if they had not exercised the magistracy (senatores pedarii). The pedarii had restricted the right to speak and participate in the discussion and could only vote.

At first, the powers of the Senate extended to all serious matters of public administration, except those reserved to the decision of the sovereign people (election of judges, approval of leges tributae, declarations of war and peace treaties) for which the Senate, though who formally authorized them, only he was consulted.

The creation of the tribunes of the plebs (494 BC) represented a limitation of the role of the Senate, which was confined to the upper inspection of the treasury, the appointment of legacies and ambassadors abroad, the audience of the other countries sent to Rome, the granting or denial of triumphs, to rule on the laws that the people had to vote in the comitia centuriata, to invest the consuls of imperium in circumstances of danger to the Republic, to guard the purity of the religion and, in general, to serve as the permanent council (templum sanctitatis, amplitudinis, mentis, consilii publici, caput urbis, aram sociorum, portum omnium gentium ac Regnum consilium).

Progressively, the Senate assumed the appointment of several magistracies, which indirectly involved the appointment of its members.

Over time, the Senate went from being an advisory board to the service of consuls to be an institution with executive power, which became important to have reserved the control functions of the majors magistracies (consulate and praetura), military campaign supervisory and foreign policy.

Contrary to popular belief and even in some cases could promote laws, Republican Senate was not really a legislative chamber: usually, the Roman laws were promoted by the tribunes of the plebs and approved directly by the people, after consulting the Senate (senatus consultum).

It was under the rule of the Caesars when the Senate concentrated legislative power which had the popular assemblies. However, the legislative power of the Senate in imperial times existed only in appearance, because in reality became a mere instrument in the service of the emperors.

The senatus consultum was one of the main sources of Roman law: if during the Republic had considered simple advisory opinion given by the Senate to a magistrate, under the Empire became a binding act with force of law (senatus consultum est quod senatus iubet atque constituit; idque legis vicem optinet, quamvis fuerit quaesitum). The Senate always decided on issues of common or general interest, unlike the decree of the Senate, which only gave response to issues of particular interest.

In senatus consultum appeared the date and place; the name of all attendees senators; then the proposal and the name of the magistrate who had presented and finally the approved text:

Senatus consulti auctoritas

pridie kal. octob. in sede apollinis

scribendo adfuerunt L. Domitius P. Canuleius, ...

quod M. Aemilius eis verba fecit de ...

de ea re ita consuerunt ut, ...

pridie kal. octob. in sede apollinis

scribendo adfuerunt L. Domitius P. Canuleius, ...

quod M. Aemilius eis verba fecit de ...

de ea re ita consuerunt ut, ...

When the tribunes of the plebs formulated opposition and exercised the right of veto (intercessio), at the end was recorded with this formula: Huic senatusconsulto intercessit ... Tribunus plebis.

The first step of the laws by the Senate was not mandatory, but essential, because with its powers the Senate could help or hinder without difficulty executing a text approved by the Assembly. Thus, any tribune who wanted to see properly developed program saw the need to reach agreements with the senators. In urgent cases, which usually appear in the context of war or crisis, the Senate could legislate without laws were ratified by the Assembly, subject to ratification, that by the end of the Republic it was almost never requested.

If at first consisted only patricians, from 312 BC Lex Ovinia allowed plebeian could be part of it (conscripti). Time after missing the differences between patricians and plebeians, the speech to address the senators remained "Patres et conscripti ...".

By custom, the appointment of Senator was for life, but this habit led to law only to the patricians. As the Senate represented the patrician nobility, plebeian used to be relegated to a secondary role and if anyone objected, risked losing office at reviews of senators took place every four years. Moreover, as the plebeian who entered the Senate did not on its merits but only for their wealth, class interests were often coincidents with those of the patrician nobility.

The Senate was summoned by any of the magistrates who could consult (consuls, praetors, tribunes of the plebs) and convenor presided over the meeting.

The number of senators was increasing with time: the 300 existing in the middle of the Republic, passed to 600 in times of Sulla and 900 with Julius Caesar.

Augustus reduced their number to 600 and after the war with Mark Antony in 31 BC, recovered as senators survivors of traditional families and their own supporters. Although it appeared to increase the powers of the Senate to entrust the election of magistrates (until then had corresponded to the comitia) really reduced them, since the magistrates became honorary positions and candidates they needed the approval of the emperor.

The election of senators corresponded to the Kings, after the consuls and censors and onwards to the triumvirs and Emperors (also exceptionally, the people or the Dictator: Fabio Buteo was appointed dictator with unique custom of providing the 80 vacancies that left the Senate defeat of Cannae).

Qualities. To access the senatorial rank were required:

- initially, be patrician (over time, the doors of the Senate were opened to plebeian).

- belonging to the equestrian order (previous step to access the senatorial order).

- be at least 25 years.

- possess the minimum equity fixed by law.

- have good reputation.

- not have been sentenced to degrading punishment or busy offices of low regard.

- have had with recognition a magistracy.

Their distinctive signs were the laticlavia tunic and black boots with silver bezel and prerogatives as follows:

- accommodation in a prominent place in theaters and public spectacles.

- right to attend religious celebrations and sacred rites.

- preference for positions of responsibility in legations and provincial governments.

- administer justice in matters of small importance.

- clarissimi treatment.

- special senatorial immunity.

- certain tax exemptions.

- not be subjected to torture or humiliating punishment.

Magistracies

With Magistracies, Rome replaced the leadership of kings by a new system of government: the figure of CONSUL, supreme magistrate with imperium, which received all the powers which had hitherto been the king though, hereafter to be created with a colleague and temporary. There were two consuls called ordinarii, which gave name to the year (eponymous), and one or more substitutes or suffecti. The consul led the government in Rome and in wartime, was the commander of the army. Their mandates were annual and every consul could veto the decisions of the other (intercessio). Wore the toga paetexta, used the sella curulis and it was preceded by twelve lictors (law enforcement officers escorting senior managers).

In case of external danger or serious internal disturbance, the Senate could enable consuls to appoint a dictator. The appointment, for a period of six months, concentrated the leading powers in one person and the suspension of the exercise of other ordinary magistracies.

Figure of consul was slowly formed after the fall of the monarchy. Initially coexisted the rex sacrorum in the exclusively religious sphere and the magister populi, which took over political and military responsibilities.

In the absence of written provisions, plebeian were unaware of the rules which could become tried and normally applied patrician tradition as suited their interests (mores maiorum). Therefore, one of the first plebeian claims was the organization of the Roman tradition into law. For this, the Senate agreed to send to Greece a commission to inquire about the government of the Hellenic cities and replaced the magister populi by a college of ten people (decemviri legibus scribundis consulari imperio) to draft within one year a set of rules that would regulate relations between all Roman citizens. The result was the Twelve Tables, the first legal structured text by way of basic rules of coexistence, was exposed publicly in the Forum in 451 BC.

Once approved this law, in 449 BC a magistracy of two people, which became known as praetor maximus and praetor minus was restored. Since then, this pretorial college, precedent of the consular one, would alternate with colleges of military tribunes with consular power (tribuni militares consulare potestate).

In 367 BC, the Leges Liciniae-Sextiae completed the matching process between patricians and plebeians, allowing the latter progressive access to office.

The consuls were elected by the comitia centuriata and effect of intercessio only adopted consensus decisions: only veto the other consul or the tribunes of the plebs limited their powers. Instead, the consuls could interfere decisions of other magistrates (praetors, aediles and quaestors). Its military power was unlimited and had command of two legions each.

With time and for safety, it was demanded that the decisions of the consuls were ratified by the Senate, which could thus control treaties and generally participate in decisions that transcend the mandate of one year.

Took office as the Ides of March, although from 153 BC they did it during the Kalends of January. When ending the mandate, were subject to the laws and, when appropriate, were accountable for their decisions.

By increasing the territory, some of the powers of the consuls had to be shared with provincial magistrates (proconsuls and propraetors).

To be consul was required having 40 years for the patricians and 42 for plebeians, although it was possible to hold the position more than once if between appointments passed inactivity preset time between each magistracy. Since 180 BC the Lex Vibia annalis demanded respecting the specified period of inactivity and have passed earlier by the lower courts (cursus honorum).

Other magistrates.

PRAETORS: ordinary magistrates elected in comitia centuriata. Assumed imperium functions when the consuls were outside Rome. They could also govern provinces and get under the command of legions.

Since the Twelve Tables, the magistrates assumed the function of administering justice (iurisdictio) and the ius edicendi, which allowed them to issue edicts on criminalizing illegal acts, assumed as its own the edicts of his predecessors and corrected or repealing the above provisions. Thus emerged a new law thatwas developed in parallel with the ius civile and was called ius honorarium or praetorian law.

There was only one praetor at first. In 242 BC the office of praetor peregrinus was established to resolve disputes between foreign or between them and Roman citizens. This new praetor could leave town, unlike it was renamed praetor urbanus, he could not leave Rome more than 10 days.

In 227 BC two new praetors were appointed; another two in 197 BC to take care of the needs of Hispania. Became eight days with Sulla and twelve at Caesar times.

After Lex Vibia annalis (180 BC), a minimum age of 39 years was required (in the imperial period was reduced to 30), wore the toga praetexta and for his personal safety was escorted by six lictors. In times of Julius Caesar was required only those who had been aediles could be appointed praetor, requirement that until then had not been necessary.

AEDILES CURULES: the charge was recognized as an official magistracy in 365 BC by the Lex Furia de Aedilibus (aediles plebis that had existed until then were merely auxiliaries to the tribunes of the plebs to judicial matters of little importance).

In 45 BC, Julius Caesar named two more plebeian aediles with unique features to take the control, supply and distribution of grain in Rome (aediles cereales).

After the Lex Vibia annalis (180 BC), a minimum age of 36 years was demanded for the post and also to be previously appointed quaestor.

Functions:

Functions:

- Maintenance of temples and public buildings.

- Water supply and maintenance of aqueducts and sewers.

- Care streets, paving and cleaning.

- Firefighting.

- Control of baths and taverns.

- Compliance with dress codes.

- Control of morality and public decency.

- Religious control, preventing the entry of foreign divinities and superstitions.

- Monitoring the correct use of the ager publicus

- Prices control and inspection of weights and measures of the markets.

- Monitoring slave purchases and decisions in commercial matters of minor importance.

- Compliance traditional rituals and ceremonies.

- Police and law enforcement control in Rome.

QUAESTORS: in early times had the functionof substantiate the processes that impose the sanction of capital punishment. Subsequently charged with the supervision of the public treasury (aerarium) and control of the finances of the state, the army and officials. Also supervised the games organized by consuls, aediles and quaestors.

The first quaestors, two in number, were chosen around 445 BC. In 421 BC were four, two of whom exercised by delegation of consuls treasury management (quaestores aerarii) and the other two were in charge of the budget and military spending (quaestores militum).

The nobility attempted to derive the appointment of the quaestores aerarii from the consuls to the comitia centuriata, but failed and his appointment to the comitia was entrusted to the comitia tributa, whom corresponded the appointment of military quaestors. Since then, the plebeian could be appointed quaestors of public funds.

In 267 BC two quaestors were added to control the tributes of the Italian allies in 240 BC and two for Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia.

To be quaestor was required ten years of experience in the army. After Sulla's reforms, the minimum age for quaestor was established in the 28 years to the patricians and 30 for plebeians. Elected quaestors automatically became members of the Senate. Wore toga praetexta but they were not escorted by lictors.

CENSORS: the appointment marked the culmination of the political career of a person and get the appointment was tantamount to reach the category of one of the most important men in Rome. The charge was outside the cursus honorum.

To become censor had to pass first through the consulate and only those who had big auctoritas and dignitas dared to be candidates. The were appointed two censors at a time (one patrician and one plebeian) and their positions were for five years, although in practice only really gave their duties during the first eighteen months.

Upon completed the effective eighteen months, they conducted a public ceremony of purification of the city, called lustrum. They were elected by the comitia centuriata a proposal from the consuls. They could wear the toga praetexta but had not imperium and therefore they could not take lictores escort.

They prepared the census of citizens according to their wealth, but also assumed functions on taxation, budgeting and public morality.

The office was created in 435 BC and soon became a desirable magritracy because since 312 BC the Lex Ovinia had recognized their right to fill vacant Senate seats.

Sulla abolished the office in 81 BC; was restored by Pompey and Crassus in 70 BC; Caesar returned to abolish and while Augustus recovered, the dimensions of empire made that, except with respect to the census, functions never return to be the same.

The Assemblies

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

During the founding of the city (753 BC) were established in Rome the Senate and the calata comitia.

The calata comitia were popular assemblies without vote that were active during the Monarchy. It was chaired by the Pontifex Maximus and held on Capitoline Hill. The calata comitia met only patricians organized in their curiae. Meet legal functions, including acting as witnesses in wills, probably to avoid, after the death of the testator, any dispute concerning his will.

With the reforms of Servius Tullius (578-534 BC) the importance of calata comitia was disappearing gradually emptied of content for the benefit of curiata comitia, the special training that became no legal powers, legislative or electives. They met twice a year: March 24 and May 24 in the presence of the College of Pontifexs. In the Roman calendar those two days fasti were marked by Q.R.C.F. references (Quando Rex Comitiavit Fas, a reference to the presidency of the comitia by Rex Sacrorum).

The curiata comitia functioned as the main legislative board during the monarchy, because although its main competition was the election of each new king (the Roman was an elective monarchy), also possessed rudimentary legislative powers.

Shortly after the expulsion of the last king and the founding of the Republic (509 BC), the main legislative powers were transferred to two new assemblies: the comitia tributa, where the town was organized as belonging to each of the tribes and centuriata comitia, in which the village was organized in centuries according to their economic capacity.

Later, in the context of struggles between patricians and plebeians (only the first had access to the Senate), the concilium plebis was created: a new assembly with extensive powers that only involved plebeian.

The crisis of the Republic broke the balance between the assemblies, the Senate and the magistrates, and led to the transformation of the political system, become Empire with the Principality of Augustus (27 BC).

Under the imperial system powers of the assemblies were exercised de facto by the Senate (which in turn was handled at will by the Emperor in his capacity as Princeps), although they continued formal calls for the establishment of the various elections and called on citizens to exercise their vote. In addition, the various assemblies continued to serve for organizational purposes. With the passage of time and the transformation of the political system during the low empire period, the elections failed to be convened.

The ROMAN ASSEMBLIES (comitia), which grouped the cives to deliberate and make decisions, were essential to the government of ancient Rome, and along with the Senate, the principal organs of political representation of its citizens.

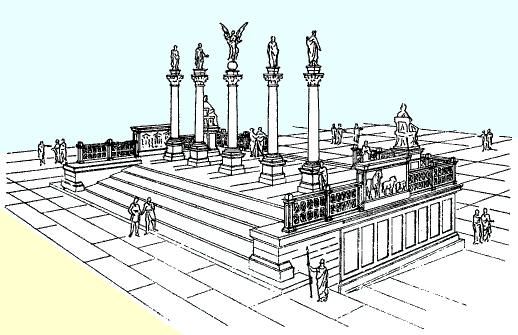

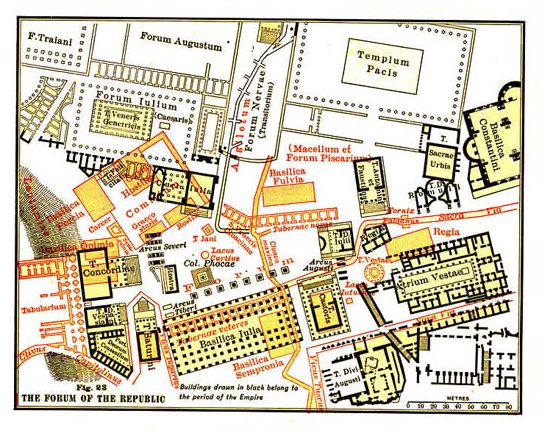

Also called comitium the physical place where the meetings were held. It was at the Forum, surrounded by temples, between the Capitol and the Palatine. It was chaired by a platform called rostra, from where laws were proposed and were made aware of the people anything that could be considered of interest. In the comitium the people chose many of its magistrates and was where candidati flocked to capture the affection and confidence of citizens.

The word rostra was used to refer to the tribune since a naval victory: in 338 BC, the consul Gaius Maenius ordered boot rams of enemy ships (rostra) to move them to Rome and placed in the wall of the podium of the Forum. Since then this platform was known by that name.

In 44 BC, Julius Caesar moved to a new location.

At the other end of the forum and part of the podium of the Temple of Caesar, a second platform (rostra divi Iuli) was decorated with rams of the Egyptian ships captured at the Battle of Actium.

Because the sources mention Rostra tria, is believed to third platform could be located in front of the temple of Castor.

In time of Augustus, the emperor had built at the entrance of comitium the called milliarium aureum, from which allegedly started to count the distance of all Roman roads.

Not existing in Rome an effective separation of powers, institutional balance was remarkably developed:

The comitia had sweeping powers, including to pass laws retroactively (ex post facto) and combined their functions with those of the magistrates, charges that otherwise were elected by themselves.

The Senate transformed from a deliberative chamber without legislative powers during the monarchy, to become the center of political power in Rome and one of the main sources of Roman law.

TYPES OF ASSEMBLY:

1. Comitium: identified assemblies held to take a substantive decision (legislative or judicial) and for the election of public magistrates. The various comitia were assemblies operating on the basis of direct democracy: all cives directly exercised their right to vote, although they did not individually, but grouped into different social categories.

2. Contio (or concio) appointed meetings that simply picked the people's voice (vox populi) through applause and boos, but such thing did not serve to settle any matter or to adopt a decision with the force of law. Usually the conciones were summoned to hear public statements (such as the edicts of magistrates) or to witness a trial or execution and without the solemnities of the comitia own procedure. The conciones were summoned by a magistrate by a crier (praeco), in what was called advocare or convocare ad concionem. In those conciones could only speak the convener magistrate or those to whom he gave the word (produxit in concionem).

3. Concilium: was a general term applied to any political meeting, which was often used to describe in Latin those of the non-Roman peoples. It was also the common term for the meetings of the Roman plebs.

Main types of popular assembly:

ASSEMBLIES IN CURIAE (comitia curiata) were the main assemblies during the first two decades of the Republic and were presided over by the consuls.

During these early decades, the people of Rome was organized in thirty curiae based on the thirty originating patrician families. The curiae created an assembly with legislative, electoral and judicial purposes that approved laws, elected consuls (the only eligible magistrates at that time) and resolved legal issues.

Plebeian could participate in these meetings, but only the patricians could vote.

Shortly after the founding of the Republic, the comitia curiata functions were assumed by the comitia centuriata and comitia tributa. Although then fell into disuse, they retained certain powers, especially to give solemnity to the appointment of the major magistrates (consuls and praetors), which were since ratified in office and invested with imperium.

ASSEMBLIES FOR CENTURIES (comitia centuriata): they voted laws and elected senators and magistrates (consuls, praetors and censors).

The creation of the comitia centuriata emptied of its powers to curiata comitia that, thereafter, only met for minor acts or protocol (the oath of consuls) to slowly disappear in the late third century BC.

The subsequent rise of the comitia tributa made them lose some of their powers.

Although initially their decisions should be endorsed by the Senate late third century BC this process was no longer needed.

They could participate patricians and plebeians, all organized in different economic classes and distributed internally in centuries.

To be located in each of them, is attending the economic status based on the territorial wealth (by area).

After the reform introduced by the law of Appius Claudius in 312 BC, the pattern of wealth ceased to be the property of the land and became calculated in terms of money, according to the following scale:

1st class: over 100,000 asses.

2nd class: between 100000-75000 asses.

3rd class: between 75000-50000 asses.

4th class: between 50000-25000 asses.

5th class: between 25000-11000 asses.

6th class: formed the capiti censi.

7th class: formed the equites.

Between the third and second centuries this pattern of wealth increased tenfold, but remained categories.

Each of the 35 tribes had 5 classes and each class had 2 centuries (senior and iunior), so there were 10 centuries by tribal and 350 centuries in total. To these had to add the 18 centuries of equites and 5 of the capiti censi (which did not appear in the census) so in total there were 373 centuries.

The individual vote was not considered in the assembly: was computed only within the century he belonged to the elector, so only influenced the final vote of that century.

Each class had the same number of votes, so that after the vote on the third (the equites voted first), was given most: 18 + [(35 x 2) x 3] = 228. Logically, the votes of the remaining had little influence.

ASSEMBLIES FOR TRIBES (comitia tributa) elected lower magistrates (quaestors, aediles), the triunviri and, eventually, the tribunes of the plebs (although the latter only by a vote of plebeian). Gradually they acquired legislative power to the detriment of the same faculty which previously performed the centuriata comitia. Patricians and plebeians included in 35 tribes.

As serving more geographical than economic criteria, were less aristocratic than assemblies for centuries. Most of the urban population of Rome was divided into four tribes against the thirty-one rural tribes. As each tribe had one vote, rural enjoyed a comfortable majority.

The extension of Roman citizenship reduced the importance of these elections: the largest number of cives not involve expanding the number of tribes, but the new citizens were included in the existing ones, which election lost their effectiveness to be impossible bringing all citizens entitled to vote, scattered throughout Italy.

ASSEMBLIES OF THE PLEBS (concilium plebis): born as assemblies reserved for plebeian, emerged as meetings with no decision-making power, but their agreements gradually gained force of law, decisions replaced those of other elections and obtained the appointment of tribunes, granting honors and even responsibility for peace and alliances.

They met on the Aventine, outside the pomerium, the sacred precinct of the city. Some sources collect that for matters of legal and administrative also gathered at the Forum and in the Capitol. The Champ de Mars was used for elections in the final centuries of the Republic.

The tribunes of the plebs (tribunus plebis) were considered plebeian counter the patrician consuls power, but only within the city of Rome. Outside the city, the only imperium was the consul or dictator.

The tribunes of the plebs were two, chosen by the concilium plebis. Later, their number increased to five, then ten, then turned back to number two.

Eventually, when the plebeians had achieved its objectives, the role of the tribuni tended to be unnecessary, representing more plebeian aristocracy to the humble, but nevertheless were not suppressed. Their election then passed to the comitia tributa.

The tribunes of the plebs had broad powers in justice (tribunitia potestas) and, in general, the relief to plebeian against the power of the patrician magistrates (ius auxiliandi). They were assisted by iudices decemviri or decemviri litibus iudicandis, acting as a jury, and in minor judicial issues, by the aediles of the plebs (aediles plebis).

The tribunes of the plebs could not vote in the Senate or be part of the city council (curia), but could overrule any Roman magistrate decision that could be harmful to a plebeian, including the consuls (ius intercessionis).

The charge was inviolable and were protected from physical damage (sacrosanctitas). On an annual basis, must necessarily lie with plebeian.

They had no proper consideration of magistrates, so they could not sit on the sella curulis not wearing the toga praetexta and had no lictors, but instead had the right to convene the comitia centuriata.

Sulla severely cut his powers, eliminating the veto and ability to propose to the assembly laws without the consent of the Senate, but during the consulship of Pompey and Crassus, the charge was restored with the same previous extension.

Augustus received all the powers of the tribunes, although being legally impossible for a patrician to aspire to the office of tribune of the plebs was never formally held the title. The tribunicia potestas was one of the main bases in which Augustus based his authority, the other being the imperium proconsulare maius, giving him veto power and authority to convene the Senate.