Roman coinage

Coinage in the Roman Republic is late when compared to the rest of the Mediterranean countries, especially Greece and Asia Minor, where the coins were already known in the seventh century BC.

Before the introduction of the currency, the two most common means of payment in the Roman economy were cattle (pecus), whence the Latin word for money (pecunia) and the bronze pieces known as aes rude (rough bronze), irregularly shaped, variable weight and of doubtful utility if you consider that should be weighed before each transaction.

Until the end of the fourth century BC bronze began circulating in flat bars. These rods, called aes signatum (bronze signed), weighing about five Roman pounds at the rate of 324 grams per pound (327.453 according to different opinion) and showed signs or pictures on one of their faces or both. Although they were a means of payment, coins were not strictly because they were never adhered to a standard official weight. Aes signatum production lasted until the end of the First Punic War in 240 BC.

The earliest forms of actual currency were melted lead and bronze pieces or aes grave (heavy bronze), which were made in mints by three specially appointed officials to the effect that were organized in a public office (tresviri monetalis). It is unclear when this office was erected, but it seams that it was early after the Second Punic War (200 BC). The three members of this office, called monetary magistrates, were responsible for emissions and were officially known as tres viri aere argento auro flando feriundo, a long title often abbreviated III.V.A.A.A.F.F. (the three men responsible for the foundry and minting bronze, silver and gold). Corresponded to these judges choose designs and specify the legends of coins, election that soon was used as an advertising medium for the benefit of their families with distinct political purposes.

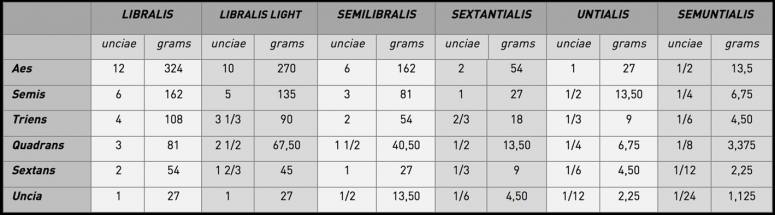

The standard coin was the as, representing the unity of libral system (aes libralis). The as was the first coin that had a circular (280 BC), had varied designs, incorporating the mark I and weighed one pound (litra), the current equivalent of 324 grams, ounces fractions of 27 grams (unciae), to rate of 12 ounces per pound.

This relationship is changed repeatedly in a short time, making it possible to find the same Republicans dies asses with different weights.

About 269 BC the weight was reduced to 270 grams and 10 ounces per pound (light libral system) and remained so until about 218 BC.

About 269 BC the weight was reduced to 270 grams and 10 ounces per pound (light libral system) and remained so until about 218 BC.

At the beginning of the Second Punic War, lightly pound dropped to retrieve the reference 324 grams.

Quickly, the successive devaluations contributed semilibralis aes 162 grams (6 ounces) and later the aes trientalis of 4 ounces, the aes quadrantalis, of 3 and aes sextantalis of 54 grams (2 ounces). A mid-second century BC again weight declined (aes uncialis of 27 grams or 1 ounce) until, after a hiatus during which ceased to be coined, the Lex Papiria (91 BC) finally set at 13,5 grams or half an ounce (aes semiuncialis). With the latest releases of L. Cornelius Sulla ended its decline until it ceased to be minted in 47 BC.

At the end of the Second Punic War (aes sextantialis), asses ceased to be melted and the aes sextantalis become coinage.

As' weight evolution

Initially the asses held a regular pattern, representing Janus on the obverse and ship's prow on the reverse. However, during the second century BC, the as left to incorporate symbols that had been used until then and replaced by legends of the gens that minted them.

Next to the as they appeared its multiples and divisors with weight changes of the reference unit, followed his luck in subsequent years.

- Among the multiples, the dupondius represented the bust of Roma on the obverse and a six-spoke wheel on the reverse, mark II and worth two aces or twenty ounces.

- Among the dividers:

- semis showed the head of Saturn, mark S and value half as or six ounces.

- triens showed the head of Minerva, mark four points (....) and amounted to one third of as or four ounces.

- quadrans showed the bust of Hercules, mark three points (...) and value a quarter of as or three ounces.

- sextans showed the head of Mercury, mark two points (..) and equivalence a sixth of as or two ounces.

- and uncia reproduced the head of Rome, mark a dot (.) and value of one twelfth of as.

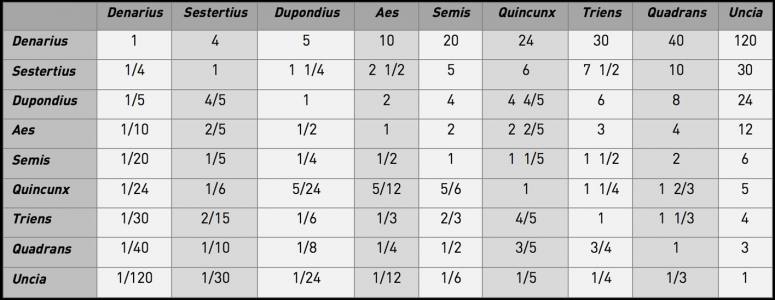

Equivalence and signs of value (libral system)

Silver coins were issued in small amounts until the introduction of the cuadrigatus and the victoriatus.

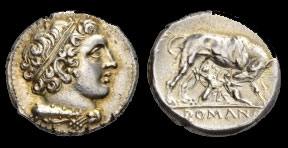

The quadrigatus was a silver coin that began to circulate from the year about 225 BC. The obverse showed the bust of Janus and the reverse Victory driving a quadriga and the inscription ROMA below. Their value was the equivalence of 15 asses and weighed as a didrachm, about 6.8 grams, but was devalued several times in succession until have less than 30% silver during the Second Punic War.

The victoriatus was also a silver coin that appeared between 221 and 170 BC with a value of half quadrigatus. It weighed about 3.4 grams and represented Jupiter on the obverse and on the reverse Victory placing a crown on a trophy with the inscription ROMA in exergue. The victoriatus was introduced about the same time that the denarius but was minted with silver of lower grade. Its value was about 3/4 of denarius, although when the quinarius was reintroduced in 101 BC with a similar type, its value was reduced to 1/2 denarius.

In order to end the wide variety of coins in circulation, the Senate proposed to generalize a type of common currency for all Italy and centralize its coinage in the mint of Rome. This new currency would be legal basis of the relative value of the bronze and silver: the exchange rate prevailing between the two metals.

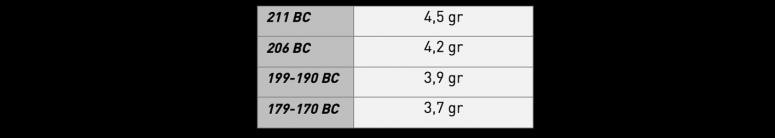

The new currency, the denarius was introduced in 211 BC and became the main coin of Rome for more than four centuries.

The denarius was silver, worth 10 asses, as ten asses equal one silver coin from Taranto, and weighed 4.58 grams (72 per Roman pound and a little more if the ratio is calculated with the Greek drachm), although shortly after its nominal weight was reduced to only 3.9 grams. Its brand value was coined X and wealth from silver captured in the sack of Syracuse in the previous year (212 BC).

The denarii were used only in medium and large transactions, leaving the general use of as for minor.

But soon it became clear that as was too small and that the arrival of the denarius had become simple enough for the particular trade coins. Over time minted silver coins two intermediate profile: the quinarius (half denarius or five asses, marked V) and silver sestertius (quarter denarius or two asses and a half, marked IIS), all with the bust of Rome on the obverse and the Dioscuri riding on the reverse.

In this context, both bronze asses and their fractions (now all coined instead cast), as the continued victoriati circulating in large quantities. Instead, quadrigati were withdrawn almost immediately.

With regard to gold emissions, after staters and half staters struck at the time of Second Punic War, appeared three new coinage worth 60 asses (Crawford 44/2, marked LX), 40 asses (Crawford 44/3, marked XXXX) and 20 asses (Crawford 44/4, marked XX).

All three show the head of Mars on the obverse and an eagle with spread wings standing on a beam on the reverse. The eagle remember what had been a symbol of the Ptolemaic coin from the beginning of the century, allowing Ptolemy IV Philopator think that could have provided gold for these emissions as a counterweight to the participation of Philip V of Macedonia off the Carthaginians.

During the next forty years, the weight of the denarius was reduced slowly. The cause is not known with certainty, but may well have been the constant wars and the high debt that was not paid in full until Gnaeus Manlius Vulso returned with the spoils of Asia after the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC). From 72 units per pound spent 84 per pound, but from that moment the denarius weight retained a remarkable stability.

Denar's weigth evolution

During the Republic, the silver content of the denarius remained well above 90%, usually greater than 95%, except for the last Marco Antonio emissions, especially given the huge amounts of Legionnaires denarii posts in fair circulation before the battle of Actium (31 BC) and coined, according to some hypotheses, with silver from Egypt provided by Cleopatra.

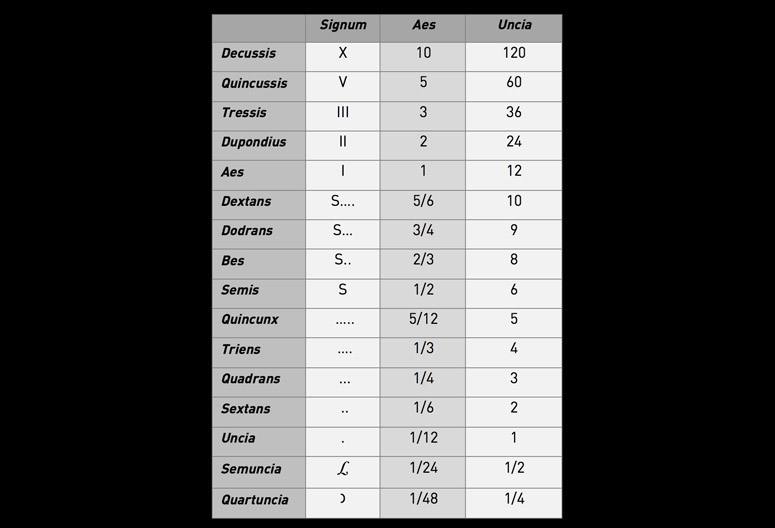

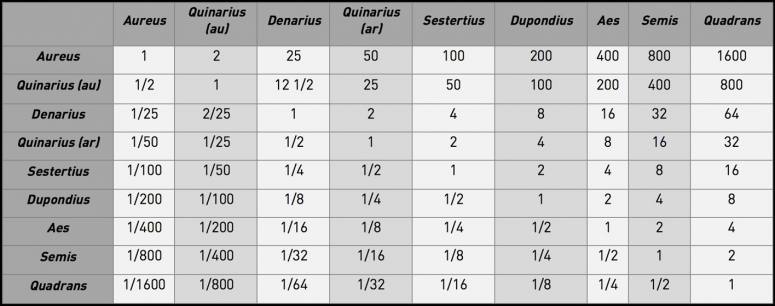

Equivalences untill 141 BC

Around 141 BC denarius equivalence was established in 16 asses, a circumstance which was taken on the obverse of the coins with the mark XVI. The change is observed for the first time on denarii of the gens Iulia, dated the same year (Crawford 224/1).

The mark XVI was soon abbreviated with an X crossed in the middle by a horizontal bar, sign that is interpreted as a monogram of XVI with all the overlapping letters (ж).

The new equivalence meant a new ratio for quinarius, happened to be worth eight asses, and for sesterces, which became assert 4. Almost simultaneously, the as was no longer considered the unit of account and was replaced in that capacity by the sestertius.

Equivalences since 141 BC

The coins of 60, 40 and 20 asses stopped immediately and emissions minted in gold not reappear until Sulla tried to raise funds for the war against Mithridates VI of Pontus, just after the financial strains caused by the Social War.

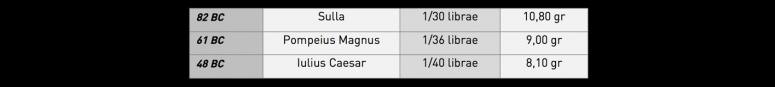

This coinage of Sulla is considered the first aureus in history (82 BC) and except for that of Pompey the Great in 61 BC (Calicó 35), there will be no other emissions gold until Iulius Caesar, who coined large quantities in the preparation a war against the Parthians that would not arrive in time to achieve. After the fall of the Republic, notably increased use during the pre-imperial era and especially in the imperial: the aureus appeared with the double purpose of facilitating large commercial enterprises and replace the staters of Philip II of Macedonia, very common in Rome for a coin that also keep it simple relationship with silver: an aureus equivalent to 25 denarii and 100 silver sestertii.

Aureus' weight evolution

In time of Augustus, probably around 23 BC, Rome mint resumed its activities after two decades without production. This coincided with a reorganization of the monetary system inherited from the Republic which intended, without altering its foundations, solve some of the problems that had affected their performance regularly.

The aureus minting followed by the standard of 1/40 by Roman pound (about 8.10 grams) with a regular weight and high purity. Republican denarius standard 1/84 per pound (about 3.86 grams) was respected and quality was improved from their silver content of 92 to 98%.

The most significant innovations were minting gold and silver quinarii (although emissions were sporadic and low volume) and on the coins, which again wedged on a regular basis to overcome the problem that their scarcity represented in trade everyday.

- The sestertius, not issued for a long time, now coined in oricalc (copper and zinc), becoming the main currency of base metal (four asses).

- The same alloy was used for dupondius (two asses).

- Instead, smaller fractions, the semis and the quadrans, were minted in copper.

Thus, it is retold, after many decades, with a wide range of dividers suitable for the various functions of money from hoarding and large payments, to purchase items and basic services.

From 23 BC, in new coinages of the mint of Rome's mention of tresviri monetales, who returned to take charge of overseeing the monetary production is observed: Augustus initially reduced their number to three (had previously been raised to four by Iulius Caesar) but in 5 BC again increase to four.

In the coinage by the triumvirs reappear allusions to his aristocratic lineage, as had happened during the Republic but now combined with representations of Augustus and various symbols designed to pay homage to the emperor.

Besides Rome, followed minting coins in East cistophori in the mints of Ephesus and Pergamum, and other currencies in Antioch. In the West, the center of monetary production started in Hispania (Emerita Augusta and Colonia Patricia), where it was available resources provided by the rich mines of the region.

From 15 BC, the production of these mints was complemented by the establishment of a new monetary production center in the city of Lugdunum, which soon gained special importance. Located at the confluence of the Saone and Rhone rivers, the gallic city was chosen for its excellent river connections and its strategic position midway between the Hispanic and the German border where the largest concentrations of troops were and therefore where the Roman administration conducted its biggest payouts. The new mint definitely replaced the Hispanian mints.

Lugdunum was also an imperial province capital, governed by Augustus without interference from the Senate. By virtue of his imperium, Augustus could mint coins there completely independently of the Roman magistrates. The measure was reinforced by the removal of the coinage of gold and silver in the mint of Rome (12 BC), which was reduced to emissions in bronze and smaller dividers. From 4 BC the mint of Rome completely shut down operations. When resumed activity in 15 AD only asseswere minted, with results similar to those of two decades before but now without the names of the tresviri monetalis, who had gone. However, the tresviri were not suppressed at all and remained until the third century AD.

The division in the production of currency (precious metals in Lugdunum and the other in Rome) would be preserved by all the emperors of the Iulius-Claudian dynasty, until the monetary reform of Nero forced to concentrate all the minting again in the imperial capital.

The reform of Nero reduced the weight of the aureus to 7.27 grams and this of the denar to 3.41 grams (1/96 of Roman pound). The purity of the silver denarius was also reduced to 90%.

Under the government of Caracalla (215 AD), the aureus was devalued to 1/50 of a pound (6.48 grams) and coined antoninianus, new silver coin which had appointed an official equivalence of two denarii. The term numismatist is a derivation of the name of the emperor (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus) to refer to a currency whose real name is unknown.

Since its silvery content was never greater than 1.5 times the denarius, emissions caused an inflationary process and accumulation: it was commonly recognized that the new currency had an intrinsic value smaller than the previous despite being top official value.

In addition, the shortage of silver reserves of the Empire, the stagnation of conquest and annexation of new territories, depletion of Iberian silver mines and needs money to pay the troops and buy their loyalty, caused each new issue of antoniniani had less money than before, into an alloy fleece.

With a weight of 5.45 grams and a diameter of 22-24 mm, completely replaced the denar during the rule of Gordian III.

During the reign of Gallienus (253-260 AD) the silver content decreased to levels between five and ten percent of the total weight. Aurelian (270-275 AD) again altered metal content of the coin, leaving a silver ratio of 4.76% (XXI or KA) until after the economic reforms of Diocletian antoninianus stopped to be coined in the year 305 AD.

The reforms of Diocletian (284-305 AD) completely transformed the Roman monetary system.

- The nummus or follis and its radiated fraction, replaced the old sestertii, dupondii and asses as bronze denominations. These new coins were minted in various imperial mints during the first decade of the fourth century AD. By mid-century, they began to move other pieces in bronze that today are known only by their diameter in millimeters: some numismatists have called centenionalis or maiorina to the largest of these coins.

- The argenteus, new coin whose high metal content caused widespread accumulation and later, as a result, subsequent abandonment.

The transformation continued with Constantine (306-337 AD), which introduced:

- solidus and its fractions: the semissis (half solidus) and tremissis (one third). The solid replaced the aureus as the standard gold coin during the Roman Empire.

- siliqua, silver denomination, along with its fractions, was coined until well into the Byzantine period.

- miliarensis also in silver, lesser in number and larger than the siliqua.

The indicated reforms affected both the weight and other characteristics of the coins as its design: while the obverse still contained the bust of the emperor, reverse types were highly standardized in all the mints. It was not uncommon representing an important idea was used in all of them together for years.

Throughout this period became prevalent mark coins with the aim of identifying the mints and the offices of origin.